In the week leading to January 27, 2024, I found myself in the audience of a fiery exchange on a WhatsApp group. The bitter exchange had begun when one of the group’s members (let’s call them A) had suggested that an upcoming hike slated for Saturday, January 27, be pushed to Sunday, January 28, so as to allow the group’s members to attend the march against femicide that would be happening on January 27. In response, another member (let’s call them B) stated that the initial date be maintained since not everyone in the group would be going to the march.

Seemingly agitated, A responded by saying that it was insensitive for the group’s members to act as though such a monumental march happens just “any other day” by choosing to attend the hike instead. Not one to easily back down, B retorted, “While I have nothing against the march, I think it’s absurd for you to label all of us insensitive for not sharing the same opinion as you,” before adding, “Speaking for myself, I don’t get how you think a march is going to heal psychopathic men.”

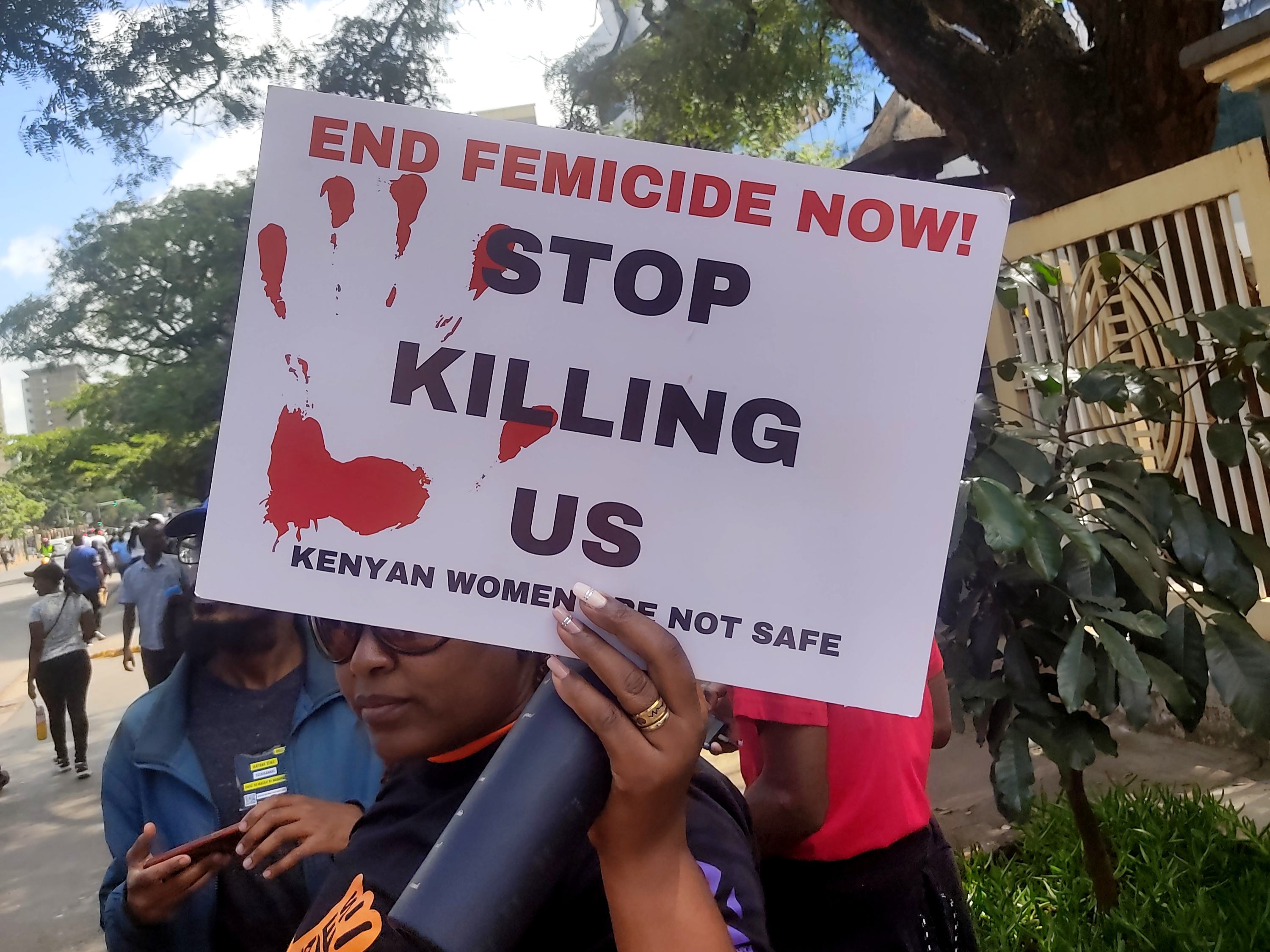

Upon switching tabs to X (formerly Twitter), I stumbled upon a similar debate. On one side was a group of folks who were eagerly looking forward to the march, relentlessly pushing the hashtag #EndfemicideKe. On the other hand, there was a group questioning the effectiveness of the march. One of the X users on the opposing side would ask, “When you say ‘stop killing us’, who exactly are you addressing? Seeing as not all men are perpetrators.” Another X user expressed scepticism towards the march stating that most often, such marches are an opportunity for “certain individuals to promote their selfish interests and gain publicity”.

The march against femicide had been prompted by a spate of gruesome murders of women. On January 3, the body of 26-year-old Starlet Wahu had been found in an Airbnb apartment with several stab wounds after a short stay there with a man she had met online. Less than a fortnight later, on January 14, the decapitated body of Rita Waeni, a student at the University of Nairobi, had been found in a trash bag in a Nairobi Rental apartment. According to data from media and research firm Odipo Dev, at least 14 women had been killed between the start of the year and January 27. Moreover, in 2023, Femicide Count Kenya reported that it had recorded at least 150 killings – the highest in the past five years.

Reading and listening to the debates and counter-debates online two questions arise. First, why have femicide cases been on the rise despite Kenya having a Sexual Offences Act that criminalises violence against women and the Kenya police having a specialised desk for reporting gender-based violence cases? A number of reasons have been fingered. One of them is the sluggish and ineffective Kenyan justice system that is marred with corruption and tardiness in prosecution. A proper example is the unresolved case of Sharon Otieno’s murder which happened in 2018 – close to six years ago. Another reason is what many describe as “deep-seated misogynistic nature and patriarchal ideas” that have designed Kenyan men to see women as objects to be owned and that focus on blaming them for being victims rather than the male perpetrators.

The second and most consequential question as brought out by the online conversations is, how effective is the End Femicide march in addressing the femicide malady?

The following are interview excerpts from a few people I talked to concerning their views on the effectiveness of the march.

Eric, 32

More than anything the march was a statement. It mainstreamed the terminology “femicide”. Ipso facto, this is a success because this is a feminist term, which means for people to understand it, they must mentally inhabit a feminist point of view. With this word and the fear many women felt because of those killings, and the solidarity the march aroused in them, it may be an introduction for many Kenyans to the ideas espoused by feminists. Language is a key part of any revolution because you can’t introduce a new way of thinking if you stick to the same old words. So a term like ‘femicide’ becoming mainstream here in Kenya is a major win for the march.

Wandia, 45

To begin, I have to state that femicide is very wrong and inhumane. I also do not like the victim-blaming around the whole conversation. Looking at the matter closely, I think many more people are not mentally okay. I mean, if you look at the nature of some of these killings, take for example the case of the late Rita whose body parts were dismembered, the sheer brutality of it all points to deeper underlying problems that are more likely to do with the perpetrator’s state of mind. It seems as though the perpetrators are projecting their mental unwellness to their victims. That said, I appreciate the fact that the march helped to create more awareness about femicide. However, I do not think it will help much in changing the situation. As long as the salient problems – like the fact that many more people are suffering mentally and psychologically – are not addressed, then these cases will keep coming up.

Cindy, 22

The march helped to create awareness in a very big way. Since the march, I have noticed growing sensitivity towards the subject of femicide especially in conversations. Another very important development is that more talks about femicide and gender abuse have started online. People have started to openly share personal experiences since there’s perceived support. However, I think that all this is a gradual process. The effects of the conversations happening now will take time to manifest especially because the legal and policy mechanisms still have glaring holes.

John, 52

The march was only effective in creating awareness. Just that. The truth is that the roots of the problem have not been addressed. The femicide and gender-based violence cases are driven largely by the fact the socio-economic problems Kenyans have been facing for the past say six or so years have badly damaged interactions within society. While the prevailing problem is femicide, if you are keen enough to look, the number of men who are victims of gender-based violence and some of whom have gone to die in the hands of their wives or female partners has been on the rise too. The reason why these things are happening is because when people lose the sense of predictability in their lives, it affects their psyche in a big way. It increases stress levels and with fewer alternatives for release, their partners are likely to become victims. To effectively tackle femicide and all the gender-based violence happening, we need to first have a serious conversation within society about how we can chart a path to healing our scars.

Wrapping up

A research report by the Advancing Learning and Innovation on Gender Norms (ALiGN) movement reveals that occupying public space such as through performance or protest is important in renegotiating prevailing gender norms and social relations. According to the report, mobilisation and activism bolstered by education efforts produce new narratives, calling into question gendered assumptions. Additionally, those who get involved in mobilisations of any nature, also change their own interior narratives thus transforming perceptions of themselves and of other women in their families and neighbourhoods.

In writing about the ALiGN report, Caroline Harper says that benefits resulting from the agitation by social movements may take time to accrue. She also emphasises that for such protests to achieve their purpose, they must be accompanied by agitation that targets policy and legal reform. Additionally, Caroline emphasises that society ought to re-think how it socialises its children and how social media content influences their attitudes and behaviours towards gender construction.