Islam swears to care for and protect its women. However, the actions within the community are often telling a different narrative.

When I was featured in the Daily Nation after the launch of Unfit for Society in 2018, it was less about my book and more about my life. Inferiority complex convinced me that I didn’t have much to tell the world, and that nothing I had to say mattered. So, I said the least I could, yet it was still intense because mine is a life marred with troubles almost since it begun. I talked about sexual harassment and rape, and I was scared that my world would come crumbling down, though it was really a small world that was just beginning to rise. To my surprise, when the paper came out, many people who read it reached out with so much compassion and understanding.

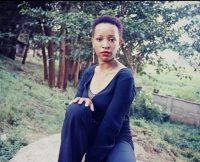

Cut to my hometown where my mum was working hard to hide the paper from my father. The reason being, in the featured photo, my hair was uncovered and that trashed everything else that came with it. She herself questioned me, but she wasn’t hysterical about it. However, we both knew that my father’s reaction would be nothing short of violent, either verbal or physical. I wasn’t hurt per se, but I wished, for a moment, that things were different. My father is a staunch Muslim and so liberalism and choice weren’t popular words in our home. But for some reason, he gave us the gift of education which he, on occasion, says has ruined me for Islam.

The ongoing riots and the unfortunate predicaments of the Iranian women bring up a lot of emotions for me, the most prominent being empathy. When reading Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran, I felt relief over the insignificance of my own experiences. And isn’t that the point, learning other people’s tragedy to make you feel better about your own troubles?

“…how well could one teach when the main concern of university officials was not the quality of one’s work but the colour of one’s lips, the subversive potential of a single strand of hair?”

That subversive hair mentioned in Azar’s book is what led to the death of the 22-year-old Mahsa Amini.

“The pressure was hardest on the students. I felt helpless as I listened to their endless tales of woe. Female students were being penalised for running up the stairs when they were late for classes, for laughing in the hallways, for talking to members of the opposite sex…In between bursts of tears, she explained that she was late because the female guards at the door, after finding a blush in her bag, had tried to send her home with a reprimand.”

Each of Azar’s student brings a different aspect of the regime to the room and they all collectively, yet fearfully, agree that things have gone too far. The discussions they have in that room unveil themselves and their fears. They disclose the atrocities they face, the witch-hunt on professors and lecturers, the ban on books and everything aimed at keeping the community, especially the women, in check. One gets the feeling that the entire regime’s foundation exists solely to control and impose on women.

To an ordinary ear, it might sound far-fetched to say that women were penalised for laughing, but I have heard it within the walls of my father’s home, the shamefulness of a woman’s laughter or voice. It is the premise for women not calling for Aadhan because what if her voice is too sexy and a man, instead of heeding the call to pray, feels the urge to have sex?

Ayaan Hirsi boldly wrote about the crimes of religion against women, her own experiences taking the lead in shedding light on what the behind the scenes of otherwise respected families looked like. Her vulnerability was rewarded with death threats and contradictions. I felt at home with The Infidel as I did with Reading Lolita in Tehran because I immediately understood that these were not lies being perpetrated against the Muslim community.

Islam in itself does take pride in being a religion of peace, but it is also on the account of the same religion that Ayaan’s producer – Theo Van Gogh – was murdered on 2nd November 2004. It was also the foundation for the attempted murder of the author of Satanic Verses, Salman Rushdie. While we neutralise Islamophobia by highlighting the positives of Islam (and those positives are many), we must acknowledge the challenges of the people trapped within the religion. This is either because of their families or regimes whose idea of an Islamic republic is confounding women to a life of near inexistence, of being visible as little as possible, of being accepting of all that is imposed on them, and following meekly the holder of the chains around their necks.

The idea that any state or republic could be a monotheistic state is absurd. It is an era of freedom to choose to believe or not to believe. Yet, in the heart of a world overpouring with the illusion of freedom, there is an old man walking onto a stage with a walking stick claiming that the riots are fuelled by the US. There can be no fire to fuel if there wasn’t a spark of discontent among the women of Iran, and neither US nor Israel nor Iran needs to tell women how to dress.

The Muslim men who must be protected from women’s hairs, nails, eyes, bodies and existence, must find a new way to take responsibility and control themselves. If there is so much horniness brewing in them, maybe they should fast all year round and confine themselves within the walls of the Mosque until they are sane enough to be released into the world.

I hope the women of Iran find their freedom, to veil or not to veil, to be Muslim or otherwise. And if they choose to hide their hair, I hope that if one day, a subservient strand shows, there will be no moral police to take their lives.