A woman's journey in conservation shouldn’t come down to sacrificing one thing for the other—the workplace should enable and support that holistic life.

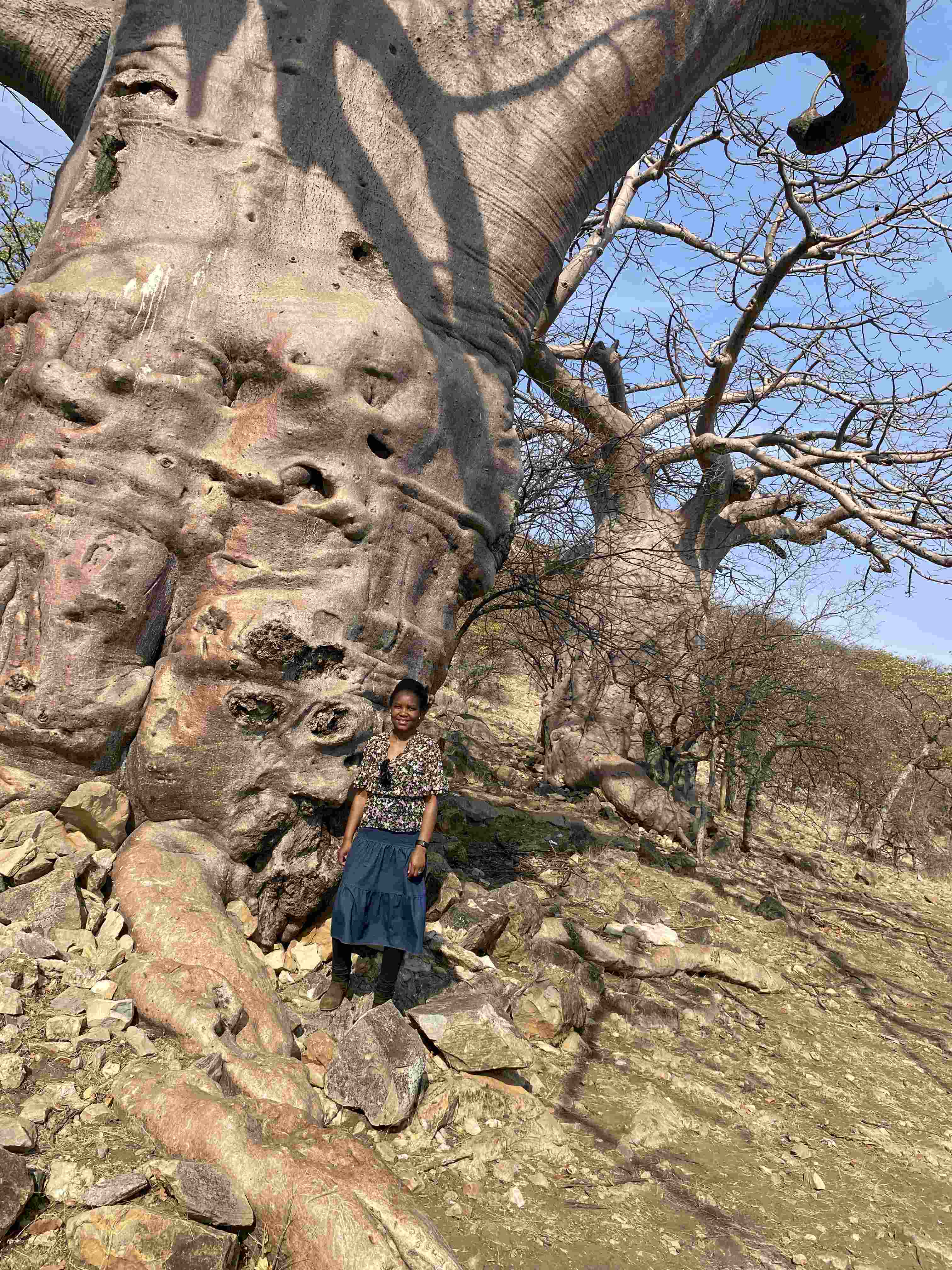

Basilia's humble upbringing in a small village north of Etosha National Park in northern Namibia played a crucial role in shaping her character. Living in this close-knit community, she learned the importance of strong communal bonds. Engaging in traditional subsistence agriculture during her formative years instilled values of interconnectedness with nature.

She has accumulated 20 years of hands-on experience in various fields, including community-based natural resource management, sustainable tourism, local economic development, environmental education, and project management. She has supplemented her practical knowledge and experiences with two master’s degrees: an MSc. in Biodiversity Management and Research from the University of Namibia (in collaboration with Humboldt University of Berlin) and an MBA from the African Leadership University.

Basilia works at IRDNC (Integrated Rural Development and Nature Conservation) in Namibia. As an African woman leader, she is dedicated to driving change and rewriting the narrative for effective contemporary African conservation leadership.

The Women for the Environment 2023 fellow shares insights from her journey with Damaris Agweyu.

Basilia, what does success mean for you?

Seeing my family happy, seeing other people succeed, and just being me. It's not about making a lot of money, trying to change the world on a grand scale or measuring myself against what others have achieved. It's about setting and achieving my personal goals and seeing others thrive at their own pace.

What does "just being you" translate to?

Bringing my authentic self into situations. This means staying humble, empathetic and kind.

Humility carries different connotations. What does it mean for you?

It isn't submissiveness or allowing others to walk all over me. It is acknowledging that no one person is less important than the other, regardless of social status. It is recognising that I am not perfect and neither are others.

I don't see humility as a hindrance to ambition. I still fight for what I think is right—but with kindness and respect. As a conservation leader, humility helps me remain grounded and prevents me from being carried away by “power abuse” tendencies.

How did you end up in the world of conservation?

Since childhood, I've always been deeply connected to the land as a daughter of subsistence farmers in a rural village. After completing my undergraduate studies, I joined a sustainable tourism company which had a small environmental department. I got involved in internal environmental audits for all their lodges in Namibia. I was also responsible for raising awareness among our staff about eco-friendly practices.

The organisation also had a joint venture with local communities to generate income through tourism. At that time, I found it very noble, and during that process, I became very interested in conservation, sustainable tourism and community.

My first work trip in the field was to the Kunene region, which is very beautiful with its rich biodiversity and desert-adapted elephants and rhinos. This caught my attention, and I decided to do a master's in biodiversity conservation and management. I conducted my research in Kunene. Working on my research while living in a tent for about two months and discovering this rugged yet beautiful landscape made me fall in love with the environment. That experience also solidified my connection to Kunene. Until now, I don't know if there's anywhere in Namibia that I'm more fond of and connected to than this region.

After working for the tourism company, I transitioned into environmental consulting for a few years, which broadened my skills and technical exposure. Eventually, I returned to Kunene and started working with IRDNC.

Reflecting on my journey the other day, I realised that half of my professional experience has been with IRDNC.

That's some serious loyalty.

It has been very fulfilling. I feel very fortunate to be part of an organisation that's played a huge role in pioneering community conservation in Namibia, addressing socio-economic and environmental injustices in a post-colonial era, and empowering communities.

You mentioned your deep connection to the land as a child. Could you share more?

As part of the Cuvelai basin system, my village was surrounded by floodplains. I imagine that a century ago, it might have resembled the Okavango Delta. Deriving food from this land, it was impossible not to feel connected to it.

Even when I went to high school about 700 kilometres away from home, nature was still a big part of my life. Again, that was a wonderful space within the mountains. During the rainy season, it was all beautiful greenery with flowers. I've never been much of a city person— until I graduated from university.

It's like, back in the day, there was this unspoken bond with the land. We took care of it because it provided everything for us. Rural communities, for example, the Kunene people, co-exist with nature and take care of the land, but as we have become more urbanised, the disconnect has grown.

In my case, after high school, there was no university in my village, and I had to relocate to the city. Fortunately for me, working in the conservation space in Kunene, visiting my parents in the village, and exploring outdoor spaces like Etosha National Park helped me maintain a connection with the land.

But the convenience of shopping for everything replaced the traditional way of growing our food—the grocery store became my land. Also, public spaces often have ornamental plants rather than food crops, so the awareness of what the land provides has diminished.

We must make peace with and adapt to this changing reality while finding new ways to instill appreciation and care for the land.

I think the critical thing is to make a deliberate effort to reconnect with nature. Many Namibians, myself included, make it a tradition to return to their villages in December. It's our way of decompressing and reconnecting. I would love to return to the village more than once a year, but the demands of work and family responsibilities make it challenging. The important thing is for me to find balance within my various roles.

As a parent who grew up in nature but you are now raising your children in the city, do you feel like they are missing out?

The first years of my life were not easy because of the struggle for independence and the fight against the South African apartheid regime. Up until the age of 10, I lived in a “war zone”. I had to deal with the anxiety of not knowing what might happen next or if my dad would come back home. But despite all that chaos, I still had a loving home. We still went to church. We celebrated Christmas. We made the best of a tough situation, and it was a very fulfilling childhood.

My children are experiencing their own unique childhood journeys, each with its own conveniences and challenges. They are obviously missing out on some of the richness I had growing up in the village, but they have other advantages that I didn’t have, for example, living in a politically stable and peaceful country, better education and learning opportunities…I only started learning English at 13, and it’s an ongoing journey.

Some of those chores in the village, especially with all those gender divisions, were a bit much. But we were subsistence farmers, and this was part of the deal. If you didn't pull your weight, you went hungry—simple as that. My father always used a saying in my language that loosely translates to: if you don’t want to work, then take your stomach and hang it on a tree. So we worked hard. But we also played hard. And we rested.

There was this unspoken agreement that after a hard morning's work, you deserved a bit of downtime. You'd wake up early and get to work. But once that afternoon heat hit, everyone would go for a nap or whatever relaxation they could find. It was like hitting the reset button. There's something enriching about it. It creates this space where you're just there. It's hard to put into words, but it's definitely different from this era of demanding professional duties and parenting, where work-life balance becomes a challenge.

I look at my son, who's ten now, and if he were back in the village, he'd probably be on goat duty. My seven-year-old daughter would probably be cooking pap at her age.

Being responsible for things at a young age taught me a lot. I mean, when you are out there looking after goats, even if it's not in a very dangerous space, it's your role to bring them back home. That’s a huge responsibility. Also, being in a boarding school 700 km away from home, taught me discipline and resilience.

I do teach my children how to be more responsible, but in a different way because times have changed. Everything's so fast-paced and exposed now, especially with the internet. Sometimes, I can't help but think it's a bit tougher for them. But they're resilient beings, and we're trying to guide them as best as we can.

What's your general outlook towards life?

Life, to me, is a constant give and take. And empathy is the glue that holds it all together. I learned this very early on growing up in a community where everyone was like family. If you needed something from your neighbour, they would give; if they needed something from you, you would give. For example, I grew up with no maternal or paternal grandparents, but there was an elderly woman related to my father whom I considered to be the grandmother I never had.

Regardless of where I am or what I'm doing, I always remind myself of my humble beginnings, where we worked hard, persevered, had hope, and were always there for each other. This is still evident in my empathetic leadership style, which I am continuously learning and unlearning.

What does an ideal conservation space look like for you?

Firstly, women shouldn't have to choose between being a mum, a wife, and a professional in the conservation space—but that's how it's designed by the patriarchal system we operate in. We constantly have to negotiate our responsibilities and time to continue doing the work we love.

When my son was around six months old, and I was breastfeeding, what mattered at that point was that I was provided with a transport system that allowed me to travel with him, in the company of his lovely and reliable babysitter, on work trips. It's a minor consideration, but these are the things that women often need to negotiate, and it's important to have the understanding and support from others so they can create that space. But negotiation shouldn't even be necessary. A woman's journey in conservation shouldn’t come down to sacrificing one thing for the other—the workplace should enable and support that holistic life.

The second thing is recognising the diverse roles within conservation. Conservationists often operate within their cocoons, but there's so much potential for collaboration. Whether it’s the ranger protecting wildlife, the facilitator navigating difficult dialogues, the philanthropist funding initiatives, the storyteller bringing attention to important projects, or the doctor bringing in wellness, more people can support conservation using their unique skills. We can create more impact if we all leverage our strengths for the bigger picture.

***

This interview is part of a series profiling the stories of the 2023 WE Africa leadership programme fellows, African women in the environmental conservation sector who are showing up with a strong back, soft front, and wild heart.