World renowned South African poet James Matthews has died at 95. His was the last great voice of an era of writers who worked against South Africa’s repressive and racist system of apartheid, which resulted in him being relentlessly harassed, detained by police and his work banned.

Schooled in District Six, an area of Cape Town where black people were forcibly removed to make way for white development, he was most famous for his poems. But he was also a journalist, cultural worker, short story writer, novelist, proponent of the Black Consciousness movement and a one-man cultural institution who never stopped speaking truth to power, even after the country’s first democratic elections in 1994.

Hein Willemse is an esteemed literature scholar who was a friend of Matthews and who wrote a book on him. He explains why the death of this remarkable man is such a great loss.

Who was James Matthews?

James was born on 24 May 1929 in the Bo-Kaap district of Cape Town, the eldest of six children. He attended school in District Six.

He worked various menial jobs. One was as a messenger running errands, what was called an “office boy”. He was later employed as an editorial clerk and telephonist at the Cape Times newspaper. He also worked as a reporter for the legendary black South African newspaper Golden City Post in Johannesburg, and later wrote for Muslim News, under the editorship of Imam Abdullah Haron, one of the first anti-apartheid activists to have died in police custody in 1969.

Even as a young boy, James was always interested in writing. Some of his teachers noted his talent and even encouraged him. Even though he left school prematurely, midway through high school, his passion endured. Matthews published his first story in a Cape Town newspaper, The Sun, at the age of 17 and from then on there was no turning back.

Initially, he wrote short stories and published these in various magazines such as Hi-Note and Drum, as well as in a collection called Quartet (1963), edited by celebrated South African writer Richard Rive. His collection of short stories Azikwelwa (1962) was published overseas. It was later republished locally as The Park and other stories (1983). He published an autobiographical novel, The Party is Over (1997), initially published in 1986 in German.

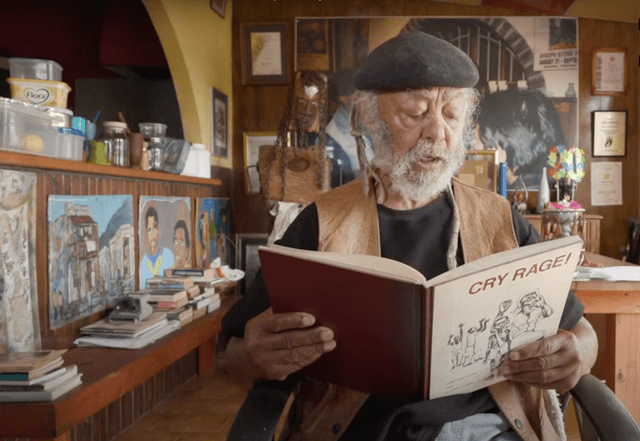

From the 1970s onwards, James almost exclusively concentrated on writing poetry. Today he is known mostly as the poet who published collections such as Cry Rage (1972), Pass me a Meatball, Jones (1977), No Time for Dreams (1981) and Poisoned Wells and Other Delights (1990). Dissidence and political militancy, infused with the self-awareness of Black Consciousness characterise his earlier poetry.

Today we think of James Matthews as an important politically committed writer, especially during the time of political and social oppression in South Africa. His was the persistent voice of political liberation and freedom of expression. He did not want to be hamstrung by authoritarian political forces, and he abhorred apartheid intensely.

What forces shaped his career?

I think the most important force in his writing career must have been the apartheid strictures forced on black people. One must remember that apartheid not only divided people into social groupings, limiting their potential. It also forced them from their land and homes, impoverished them, and destroyed their neighbourhoods, creating the fiction of them as lesser people. Matthews almost intuitively confronted this inhumanity.

In the late-1960s he found the liberation movement and philosophy of Black Consciousness very attractive, especially its core tenets of self-reliance, self-worth and its stress on the commonality of all oppressed people in the country.

His words and his opposition to apartheid landed him in the crosshairs of the apartheid government. For some time he could not travel internationally. The government banned his books and he was detained for extended periods on several occasions.

His post-1994 poetry focuses primarily on the social issues that concerned him: poverty, exclusion, the unfulfilled dreams and the politics of racial and social exclusion practised by the new government, its excesses, xenophobia. And, inevitably, ageing and death, as evidenced in his Flames and Flowers (2000), Age is a Beautiful Phase (2008) and Gently Stirs my Soul (2015).

What works or achievements particularly stand out for you?

James was an extraordinary, driven person, a non-conformist who would not allow restrictive norms to hem him in. That trait often landed him in hot water even among his friends. When used positively it led to significant cultural moments. For instance, he established the first black-owned art gallery in Cape Town, in the suburb of Athlone.

His publishing house Blac published his own work and that of other writers. In old age, he often presented poetry writing classes to learners and university students around the country.

I think one must view James’ work as a writer’s perspective on a particular environment and each of his works, his collections of poetry, speaks to a South African historical moment. I prefer to look at the whole, the impact of his oeuvre.

He was recognised internationally quite early on in his career. In the US he was awarded the Woza Afrika Award (1978), drafted onto the Kwaza Honours List (1979), and awarded a Fellowship in Writing to the University of Iowa in the US. In Germany, he received the Freedom of two cities – Lehrte and Nuremberg.

But only in the democratic era did he receive honorary doctorates and awards in South Africa. In 2004 he was awarded the National Order of Ikhamanga for:

his excellent achievements in literature, contributing to journalism, and his inspirational commitment to the struggle for a non-racial South Africa.

In 2022 the Department of Arts and Culture recognised him as “A Living Human Legend”.

How should Matthews be remembered?

Culturally, his death represents the end of an era. James has been a literary and cultural institution in Cape Town, an icon. There is even a mural commemorating his presence in one of the main thoroughfares in the city.

In South African literature he is part of a generation of pioneering black writers who truly established a tradition of resistance writing in the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. His works were among the first to be banned by the apartheid government, and he was an important voice of dissidence during a very difficult time in the country.

Internationally he has been recognised as a person of extraordinary courage and honoured for his consistent commitment to the values of justice and humanity.

***

Hein Willemse, Emeritus Professor of Literature and Literary Theory, Department of Afrikaans, University of Pretoria

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.