When Monica Kimani was brutally murdered on September 19, 2018, in her house at Lamuria Apartments in Nairobi, I had no inkling of what was coming at me. Newsrooms televised the news of the murder. Conversations about it broke out on different social media platforms.

Detectives from the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI) were under pressure to solve the mystery and catch the daring killer who left in their wake a crime scene that to many, seemed like something from a crime movie or pages of a crime thriller novel. At the time, I was preparing to attend my friend’s graduation at the United States International University (USIU-Africa) in Nairobi. Little did I know that my name was about to be dragged into a messy murder mystery I knew nothing about. My name is Brian Lesalon Kasaine, and this is a recounting of true events that happened to me.

***

Monica Kimani. She was a Kenyan business lady. On September 19, 2018, she caught a flight from Juba, South Sudan, to Nairobi. She landed at the airport in the evening. Just like any normal person, she had plans.

But who knows what awaits; where they’ll be and what they’ll be doing when death comes for them? I’ll tell you. No one knows. That is a worrying fact—a mystery of life.

In her mental book of plans, Monica wanted to spend the night in her apartment in Nairobi, and then wake up the next morning to catch a flight to Dubai. What happened next—like a horror movie scripted by the devil himself—not only cancelled her plans but also left her dead with arms and legs bound, throat slit, lying in a bloody bathtub.

The unfolding of the events surrounding her murder, as they appear in this story, is a product of my reconstruction after research and close following of the case. I had to follow it, because, as you’ll soon see, in a shocking twist, my name was involved. With that, my sanity left me and in its place entered pain, confusion and depression.

After landing in Nairobi from Juba, Monica took a cab to Lamuria Apartments and arrived in the evening. She then left the house and went to collect a delivery someone had dropped off for her at the gate. When she returned to her house, two neighbours visited; one to bring some number plates Monica had requested him to insulate, and the other to say hello. That night, a mystery man drove through the gates of Lamuria Apartments, using an identity card at the entrance to gain access. He wore a grey hoodie over a white kanzu and a cap over his head. He parked his vehicle and proceeded to Monica’s apartment. According to the two neighbours, the mystery man was well acquainted with Monica, because they hugged. The two neighbours left Monica in the company of the man. That would be the last time they ever saw her alive.

Early the next morning, Monica’s brother tried to reach his sister. His many calls went unanswered. It was unlike Monica to go incommunicado, something which sowed suspicion in her brother’s mind. He decided to go check up on her in her home. But for what awaited, nothing could have steeled him. He discovered the lifeless body of his sister in a bloody bathtub, bound like a slave, with an ear-to-ear slit on her throat. That’s when he made the call to alert the police.

One day after Monica Kimani’s body was discovered, I woke up early inside an apartment along a spruce block on Roysambu’s Lumumba Drive. I was elated for two reasons. One, it was my best friend’s graduation day, and two, my own graduation at the Co-operative University of Kenya was around the corner. I had heard about a gruesome murder but I didn’t know the details, as I’d only caught the previous night’s news in brief. I remember thinking, ‘The murder sounds like a master crime novel plot’. What I never knew, however, was that I’d soon be a character in its thickening plot.

The day ran smoothly. At USIU-Africa, I sat next to my friend’s mother and sister as he made the academic march, alongside other graduates, into the graduation square. We offered plaudits and beamed with pride as we watched him in his flowing graduation gown and square cap. That evening after attending my friend’s after-party in Kiambu, my phone rang. The caller was a friend who was in Mombasa. It had been a while since we spoke, and so I received the call with the happy tone of someone ready to launch into a fun catch-up conversation. She didn’t return the eagerness in my greetings. Her tone was urgent and disturbed, on a pendulum swinging between fear and relief.

“I’m happy you’ve picked up my call. I didn’t expect you to.” She said.

“I don’t follow.” I came back, unable to hide the confusion tuning my voice.

“I’m happy because if you’ve picked, it means that you are safe and it wasn’t you.”

“What do you mean?”

“I guess you haven’t watched tonight’s news. I suggest you do.”

Troubled by the unusual call, I fought the weight the long day pressed onto my body and trudged into the kitchen where I poured myself a glass of water. Sipping it, my thumb worked fast and brought up on my smartphone’s screen Citizen TV’s live Youtube Channel. It was about 8 p.m. and all I needed to do was rewind the live TV an hour back. There it was, as the night’s news opening story. On a red breaking news chyron superimposed on the bottom of the screen were the words: Brian Kasaine arrested.

In 2014 when I came to Nairobi and joined The Co-operative University of Kenya for my undergraduate degree, most of my friends found it tough to remember my name, Lesalon. By default, everyone, including my lecturers, went with my English name Brian, and my surname Kasaine. Later in 2017 when I self-published and launched my first book Around the Campfire, my author name went on the cover as ‘Brian Kasaine’. I went all out on social media in celebration, and to market the work. Moreover, thanks to the Personal Development Challenge (PDC) led by Cognitive Psychologist Dr Steve Muthusi of the University of Nairobi, I was sharpening my public speaking skills. Because of public lectures and poetry performances at PDC events and high schools across Kenya, Brian Kasaine became a brand in which I invested every inch of my time and energy. And now, running under Breaking News on national television: Brian Kasaine arrested. Just like that, without further details. When the anchor expanded on the news item, I realised this Brian Kasaine was arrested in connection to the Monica Kimani murder case.

I was sure of one thing, though. I wasn’t the one. Heck, I was in the safety of my house, not in a police cell, and I couldn’t see any handcuffs around my wrists. I called my friend back and said, “Hey, it’s just a case of sharing names.” I laughed. “But I’m happy to know there’s a dude out there I share a name with.” We both broke into laughter, and that was it. I filed it away in my mind as a bizarre coincidence and went to bed. But my peace, the mystery I never knew, was like a last pin standing at the end of a bowling alley, a huge bowling ball rolling slowly toward it. Matters would soon fester and the ball would knock out that pin.

My phone rang again, this time waking me from deep slumber. As soon as I spoke to one caller and tucked my phone under my pillow, another called, and then another one. It was my uncle, and then a friend, and then a lecturer, then another friend…on and on the calls never stopped. Everyone wanted to know: are you alright? Why have they arrested you?

Let me take you back to the Monica Kimani murder mystery, which by now was being unravelled piece by piece by talented sleuths.

The security guard manning the gate at Lamuria Apartments told the police that the mystery man had left in a silver Toyota Allion, license plate number KCA 031E, at around 4 a.m. The police discovered that the suspect had used a stolen I.D. card to access the premises.

A few hours later, during daybreak, in what appeared to be a separate incident, Jowie Irungu was accompanied by his then-girlfriend news anchor Jacque Maribe and their neighbour, Brian Kassaine, to record a statement with the police. Jowie was from the hospital where doctors dressed a gunshot wound to the right side of his chest after armed robbers attacked him the night before. Upon further investigations, detectives on the Monica Kimani murder narrowed down their list of suspects and landed on one man, Jowie Irungu. They investigated his gunshot wound story and found holes in the narrative. For one, there was a bullet hole on a wall in his girlfriend’s house, covered with wheat flour dough.

Moreover, the license plate of the vehicle used by the mystery man at Lamuria Apartments matched his girlfriend’s—Jacque Maribe—vehicle license registration. Much later, detectives discovered burnt parts believed to be of a white Kanzu and a cap, at Jacque Maribe’s home. The mystery man at Lamuria Apartments had been in a grey hoodie over a white Kanzu, with a cap on his head completing his look.

Here’s how Brian Kassaine, Jacque Maribe’s neighbour, fit in. He owned the Ceska pistol that wounded Jowie Irungu. Recanting his ‘thugs shot me’ narrative, Jowie had later receded to a new story: the gun went off accidentally during a heated spat with his girlfriend. The bullet struck him and left a through-and-through wound before embedding in a wall. Kassaine, the owner, gave him a distorted narrative to share with the police, that thugs shot him. He did so because the truth would land him in trouble, for the gun wasn’t legally registered.

As the wheels of this story turned, it was said that Jowie Irungu was formerly trained as a Mercenary in Afghanistan before coming back to Kenya to work as a bodyguard. The veracity of this, I can’t verify.

The three were arrested and later arraigned in court.

Unlike Brian Kassaine Spira, Maribe’s neighbour whose name has a double “s”, my surname has a single “s”. When Kassaine first appeared in court, he covered his face with a Maasai shuka to avoid the prying camera lenses of journalists. This stirred curiosity in citizens who rushed to Google and hammered in the name Brian Kassaine. When the search results came, it was me they found. A budding writer. That’s when the cyberbullying began.

Twitter, now rebranded to X, was the first platform where bullies fired shots. I’d recently opened an account. A famous influencer tagged me. Alluding to the murder mystery, he typed the caption “Writers during the day, murderers at night”. It bothered me, prompting me to write to him in his inbox. I explained that we shared names and I wasn’t the Brian Kassaine in question. He typed an apology and pulled down the tweet.

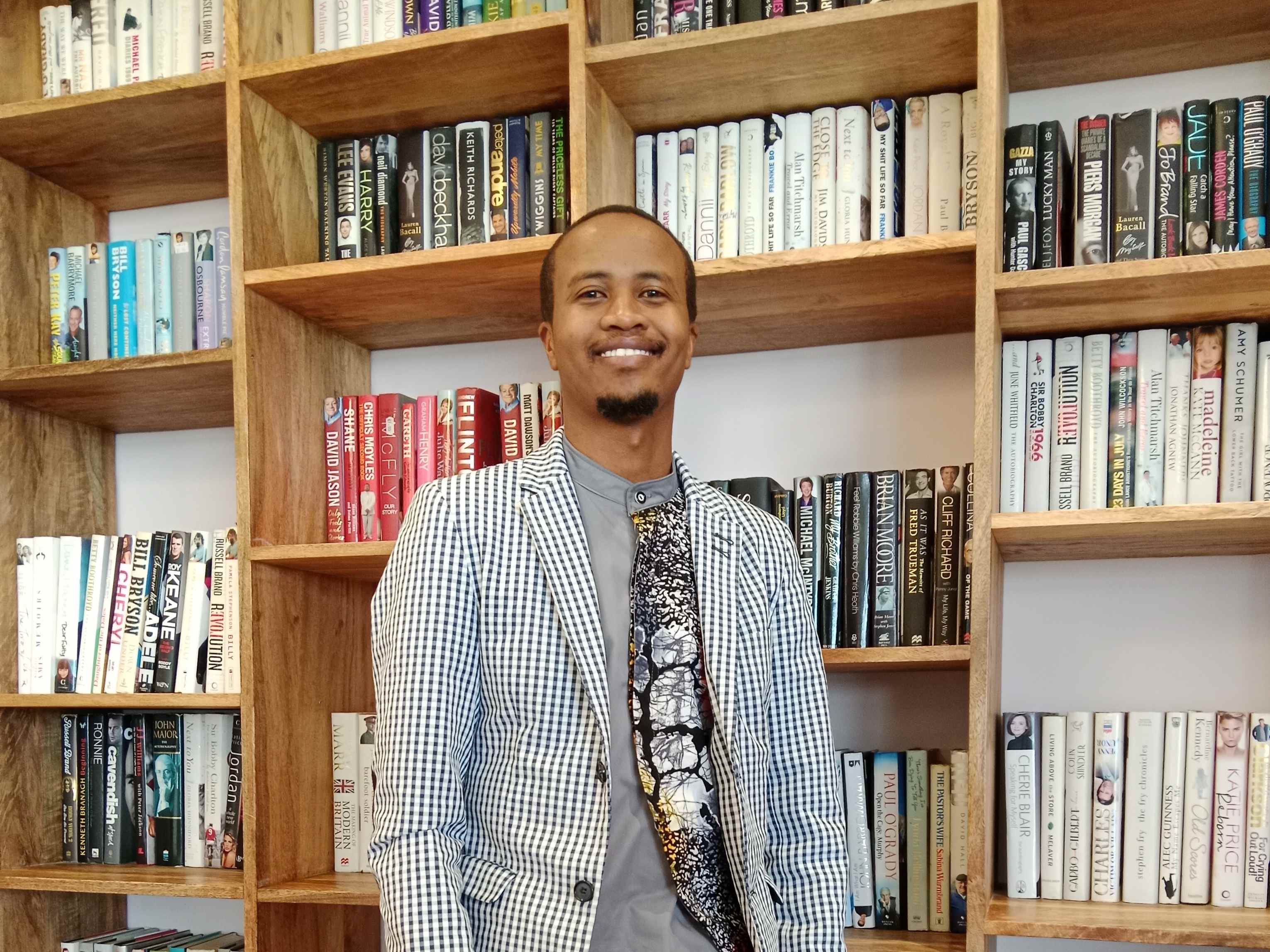

One day later, an online gutter press, The Kenyan Daily Post, ran the story of Monica Kimani’s murder. They used my photograph, one they plucked from social media, as the feature image. That turned out to be the drumbeats every cyber bully waited for to pick up their bully tools and attack me from behind their keyboards.

In the days that followed, I received screenshots from friends, taken from WhatsApp groups where my photo circulated. Someone posted my photograph on the infamous Kilimani Mums on Facebook, asking women to stay away from light-skinned dudes (like me).

If I had any hope that I’d soon wake up from the bad dream, what followed crushed them. At a hotel in Roysambu where I was having lunch with a friend, the waitresses started pointing at me. One would tap and surf on her phone and then show the screen to the other before they both started whispering behind open palms. On Facebook, a user pulled a neat photograph of me giving a speech at The Co-operative University of Kenya during the inauguration of the first Vice Chancellor, and posted it with the caption: This creative writer, a recent alumnus of Cooperative University in Karen, lent his gun to Jowie to go “commit suicide”. Was his gun licensed? Is he a robber/murderer masquerading as a writer? What’s driving these kids to engage in lives of crime?”

When I inboxed him to say it wasn’t me, he dared me to sue him before adding a comment to his post, “I hear he is the nephew to a top-shot government official, and that’s how he got the gun”.

I went into depression. Calls kept coming, and at some point, I switched off my phone. A hotel in Narok where I was scheduled to give a speech during an event cancelled our hall booking when they saw my name on the program. My low mood and message response time lacking in alacrity angered my then-girlfriend. That was the beginning of the end of our relationship. When more attacks on social media came, I turned to the bottle. Solitary whiskey to skew reality, even if for a moment. Or shots of vodka to sleep through the night.

It wasn’t until a journalist, and then a mentor advised me to report the cyberbullying to the police that I started to find calm. Cyberbullying is a crime, and I knew it, but somehow I’d lost that fact in the claws of depression. I reported the matter at Central Police Station where I was issued O.B. number 62/3/10/2018. The officer on duty then sent me to DCI headquarters in Kiambu, and I remember the sleuths joking, “Oh, so you are the one we have been looking for?” They then asked a few autobiographical questions before sending me to their colleagues at the DCI offices, Central Police Station.

Detective Andrew Fundi Njagi took my case. He listened with a tranquillity I admired, as I narrated my bad nightmare. When I showed him the messages and posts from bullies, he scratched his chin and assured me it would all go away. Detective Njagi then printed out the bullies’ messages, taking note of their accounts. He promised to contact them. In the DCI offices at Central Police Station, I sat behind a computer and my frail fingers typed out a self-recorded statement, Detective Njagi dictating the structure and required information. He then encouraged me to file a lawsuit against The Kenyan Daily Post. Which I did. But unfortunately, the dastard asswipes were hard to trace. Their servers’ location was unknown, just like the faces behind the gutter publication. My lawyer served them a letter through an email on their website. They pulled down my photograph but didn’t issue an apt apology. Years later, I gave up pursuing the lawsuit. Financial implications plus some personal reasons urged me to let up.

The cyberbullying ebbed and stopped. Sunday Nation’s Elvis Ondieki interviewed me and his article ran on page 4 of Sunday Nation on October 7, 2018, under the title Writer bullied online for sharing a name with a suspect in a murder case. Oklahoma’s NonDoc paper, where I am a contributing author, also published something about the story. I also gave an interview to KBC TV for a feature they ran on cyberbullying.

Brian Kassaine Spira later became a state witness and was exonerated and freed. Jowie Irungu and Jacque Maribe pleaded innocent and fought through many court appearances. The case came to a close after defence lawyers cross-examined witnesses. The two suspects went through the torture of waiting for their fate, with the case being postponed twice. Finally, High Court Judge Grace Nzioka read her judgement on 9th February 2024 during a courtroom session which was attended by both suspects. Jowie Irungu was found guilty of the murder of Monica Kimani, and he will be sentenced on 8th March 2024. Jackie Maribe was found not guilty and was acquitted. The judge said that the evidence presented by the prosecution did not place Jackie Maribe at the crime scene, and there was no evidence that she knew the victim.

In 2020, I self-published 3 Bolts from the Blue, a crime thriller anthology. One of my main fictional characters, a detective, is Max Njagi, a name I borrowed from the real-life sleuth, Andrew Fundi Njagi. My way of honouring him.

Five years after the death of Monica Kimani and my unwarranted cyberbullying, I’m happy. It’s all in my past and from it I picked lessons like ‘never engage cyberbullies, you’ll only feed their fire’. I also made a friend in Andrew Njagi who generously helped me with research for my book.

Until today, I introduce myself as Brian Kasaine and someone goes, “Wait a minute, it sounds familiar.”

“I know, I know,” I smile and say.

In 2020 I dropped my English name from my author name and started building a new brand, Lesalon Kasaine. Partly due to the story I’ve just shared, but also because my grandmother wouldn’t stop complaining, “We gave you a beautiful Maasai name, Lesalon, but you never use it.”

Okay, grandma. I heard you. In Nairobi, though, they love abbreviating. They call me L.K.