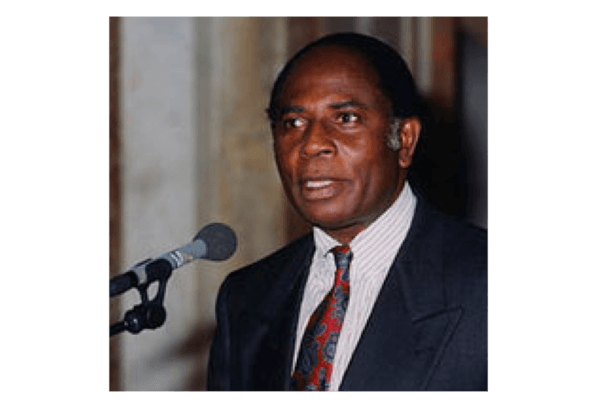

That Kwasi Wiredu was the greatest contemporary philosopher Africa has ever produced is beyond doubt. By the time of his death in 2022, the Ghanaian scholar had shaped the discourse of African thought, leaving behind a formidable corpus of writings that laid the groundwork for philosophical research on the continent.

Most of his essays championed what he termed "conceptual decolonisation", a project that advocated for a critical re-examination of African thought systems. From what appeared to be an insular exercise, Wiredu aimed to eliminate uncritically assimilated Western conceptual frameworks and revitalise indigenous African epistemologies. With this, African philosophical practices, as he envisioned, were to be both authentic and globally relevant.

Before Kwasi Wiredu’s entry into contemporary African thought, the discussion on African philosophy remained largely constrained within the conceptual framework of ‘traditional African philosophy’. This characterisation, as conceived by early scholars and anthropologists, relegated African philosophical inquiry to an uncritical inheritance of ancestral wisdom; expressed predominantly through proverbs, oral traditions and folk epistemology. It was a perspective that failed to acknowledge African engagement with the more formalised domains of philosophical inquiry, such as symbolic logic and its epistemic foundations, the philosophy of mathematics and natural science, and the moral, political and social philosophies necessitated by the exigencies of modernity.

To be sure, every civilisation possesses a traditional philosophy, an inherited intellectual substratum shaping its worldviews. Africa was no exception. However, early anthropologists, in their methodological myopia, limited their analyses to this traditional dimension, overlooking the evolution of African thought into the more analytically rigorous and systematic paradigms characteristic of philosophical modernity. In doing so, they failed to recognise that African philosophy, far from being a static repository of folk wisdom, had always been engaged in the dialectical process of intellectual refinement and theoretical innovation, similar to the paths taken by other philosophical traditions across the globe.

And so, it really posed a great challenge to early scholars, such as Wiredu, to articulate a convincing intellectual framework for African philosophy. Though Wiredu began writing relatively late—his first work appearing in the 1980s—he distinguished himself as one of the rare thinkers who distilled the fundamental tenets of what is now the widely recognised conception of African philosophy. There were, of course, other scholars of his contemporary who equally contributed immensely to this topic—like Benin’s Paulin J. Hountondji, Nigeria’s Peter O. Bodunrin, and Kenya’s Henry Odera Oruka. In fact, the tetrad formed an intellectual vanguard that would come to be known as the ‘universalist school of African philosophy’.

The central mission of this ‘universalist’ was to purge the epistemic framework of ethnophilosophy, a school of thought that had sought to encapsulate African philosophy within the confines of collective wisdom, communal worldviews, myths and cultural traditions. Pioneered by figures such as Placid Tempels in Bantu Philosophy and Alexis Kagame in La Philosophie Bantoue, ethnophilosophy regarded African thought as an inherited paradigm rather than a discipline of critical reasoning. The ‘universalists’ rejected this theory, arguing that it reduced African philosophy to an anthropological artefact rather than a domain of rigorous logical inquiry and philosophical argumentation. In so doing, they reclaimed African philosophy as a discipline rooted not in cultural description but in the universal methodologies of rational discourse and conceptual analysis.

Wiredu, though openly rejecting ethnophilosophy, did not see philosophy as entirely detached from culture. On the contrary, he recognised an intrinsic connection between the two. He employed cultural hermeneutics to diagnose three principal impediments to rational and progressive thought in African societies, namely: anachronism, authoritarianism and supernaturalism. These intellectual vices, in his view, obstructed philosophical clarity, limited intellectual freedom, and stifled social development across the continent.

To understand the weight of Wiredu’s critique, it is necessary to dissect these ‘-isms’ and their pernicious effects on Africa’s intellectual trajectory. First, anachronism, as Wiredu understood it, denotes the failure to recognise outdated ideas and practices for what they are and to discard or adapt them accordingly. Anything anachronistic is that which has outlasted its suitability. Various thoughts and ideas may fail to evolve alongside the exigencies of contemporary life. More insidiously, an entire society may lapse into anachronism if its predominant modes of thought and existence remain tied to an obsolete past. Yet, Wiredu did not see such stagnation as an irrevocable fate; rather, he believed that societies burdened by anachronistic frameworks could—and must—modernise to remain intellectually and socially viable.

Authoritarianism, Wiredu sees, is an arrangement in a society where individuals are compelled to act or endure suffering against their volition, or where the development of autonomous will is obstructed. The natural consequence of authoritarianism, he argues, is indoctrination. There has been, however, a fundamental misconception that conflates indoctrination with education. Education, in its truest sense, trains the mind to enable people to make deliberate rational choices. Indoctrination, on the other hand, is an exercise in mental conditioning, predisposing individuals towards predetermined choices. In the first case, there is free will. However, in the latter, free will is illusionary, perhaps existing in a superficial or mechanistic sense.

Still on authoritarianism, Wiredu sees traditional African society as deeply authoritarian. He observes that its social structures were deeply entrenched in a principle of unquestioning deference to authority, leaving little room for independent thought or the valorisation of originality. However, he tempers this critique with an acknowledgement that the characterisation of traditional African culture as authoritarian is a distinctly modern interpretation, formulated within an intellectual milieu vastly different from that of the past. Authoritarianism brought somewhat a communal belonging, something that was understandably necessary for the African society of the time. It would have been thus advantageous to see a judicious adaptation of this traditional culture to modern conditions by preserving good features and eliminating negative aspects, like the authoritarian ethos that once defined them.

Supernaturalism, according to Wiredu, is not the belief in the existence of supernatural beings, but associating with such belief. Such an outlook is potentially harmful to humanity, as it seeks the basis of morality in some supernatural source. Supernaturalism is the opposite of humanism, the point of view according to which morality is founded exclusively on consideration of human well-being. Our traditional thinking was intensely humanistic: what we considered morally good is what benefits a human being—what brings dignity, respect, contentment, prosperity joy to man and his community; and what is morally bad is what brings misery, misfortune and disgrace. This freedom from supernaturalism in our traditional ethics is an aspect of our culture that is worth cherishing and protecting from countervailing influences from abroad.

These vices, as Wiredu observes, confirm that a coherent philosophical tradition cannot be anchored in the vestiges of our traditional modes of thought. To seek philosophy within the confines of African customary practices is not only a misguided endeavour but also diminishing the intellectual dignity of the philosophical enterprise itself. Anthropological researches on these domains, more often than not, regard such customs as unworthy of modernity, and thus there are rarely any welcome effects that might encourage people to regard them as beneficial to modern interests. In other words, anthropologists take this research as the study of ‘primitive’ societies.

Hence, as contended above, if the philosophical salvation does not lie in our traditional background of thought, does it mean that the African must look to Europe or America? Wiredu admits that this question is wrongly put. We rather should ask ourselves what we should do with British, French, or perhaps, German philosophy. In our full awareness that our intellectual entanglement with these traditions is a consequence of historical contingencies rather than philosophical necessity, we must approach their study with a spirit of rigorous critique and methodological comparison. Acquainting ourselves with different philosophies of different cultures of the world will help us see how far issues and concepts of universal relevance can be disentangled from the contingencies of culture.

Achieving thus the above contended philosophical salvation, Wiredu proposes two underlying assumptions that must underpin Africa’s orientation to philosophy. One is that philosophy is scientific. With this, an African student of philosophy, knowing very well that the traditional African philosophy is inadequate, should acquire training in methods of scientifically oriented philosophical thinking of the type evolved where scientific and technological advance has been greatest. And two, which follows naturally as a corollary to the first, is that philosophy is universal.

This second assertion is not an easy postulate, as philosophy is, and has been, deeply enmeshed in the cultural matrices from which it arises. Philosophy is culture-bound in two respects: first, in the nature of the questions that animate philosophical inquiry, and in the substance of the theories that emerge as responses to those questions. Thus, any distinctively African approach to philosophy must be acutely attuned to the particularities of the African condition, to ensure that its concerns and intellectual inquiries remain relevant to the lived experiences of African peoples.

The second axis of cultural influence on philosophy is language itself. The very structure of a language—its grammar, semantics, and conceptual frameworks—can shape if not outright determine, the philosophical positions formulated within its bounds. Philosophical plausibility is often a function of linguistic articulation, for to learn a new natural language is, to some extent, to acquire a new philosophy. Mostly, this goes on unconsciously. An African student, therefore, not having conducted his philosophical studies in his own language, is in a position to check the philosophical presupposition of that foreign language against those of his own.

Wiredu is careful to note that language can only incline to a particular philosophy, not necessitate; so, it is easy to find, say, English philosophers who are able to resist the ontological suggestiveness of their own vocabulary. In all these, what is to be greatly emphasised is that by taking philosophical cognisance of his own language, an African philosopher might bring an added dimension to his theoretical reflection. A detailed analysis of the intricate relationship between African languages and philosophy can be found in Wiredu’s seminal work, A Companion to African Philosophy…

There is an element of solipsism whenever a comparison is made between African thought and Western thought. As demonstrated earlier, philosophical critics rarely admit that Africa is able to use the intellectual resources of the modern world to solve philosophical problems. It is for this reason that African philosophy is mostly confined to the traditional folk thought, as though it exists outside the domain of rigorous intellectual engagement. This becomes entirely different when, say, you speak of traditional British philosophy. Not anywhere will traditional British philosophy be taken in the anthropological sense. You will instead be referred to the philosophies of Locke, Hume, Berkeley etc.

The persistent anthropological framing of African philosophy, though misguided, is not entirely inexplicable. As Wiredu observes, contemporary African societies have retained strong traditional elements in the anthropological sense. It is reasonable, then, to acknowledge that African societies remain among the closest modern approximations to pre-scientific communities. This, in part, explains the enduring fascination of anthropologists with Africa. However, the error lies in the assumption that the non-scientific nature of traditional African thought is uniquely African, rather than a characteristic of all pre-scientific traditions. Western anthropologists, and many others besides, have too often mistaken contingent historical circumstances for an essential and defining African mode of thinking. The consequence of this misjudgement is the stifling of meaningful cross-cultural philosophical engagement.

When comparisons between African and Western philosophy are made on the premise that one is rooted in traditional (that is, pre-scientific) thought while the other is a product of rational modernity, the very foundations of the comparison are already skewed. Wiredu posits that Africa’s ongoing modernisation must not be seen purely in material terms but as an intellectual transformation as well. To continue to think of African philosophy through an outdated anthropological lens is to ignore the evolution of thought on the continent. Any serious interpretation of the term “African philosophy” must account for contemporary philosophical developments, recognising that, with time, the term will shed its anthropological connotations and come to signify a body of thought as intellectually rigorous and universally relevant as any in the philosophical canon.

Before this brief article ends, there is a very important question that we must address: what is the true significance of philosophy in Africa? To address this, it is imperative to give the question a more fundamental approach: what role does philosophy play in society, any society? A society is, after all, an assemblage of individuals whose actions must be governed by guiding principles, and it is the task of philosophy to elucidate these principles. It has often been said that philosophers only interpret the world, not change it. Whether this is historically accurate in a universal sense is debatable, but in the context of Africa, it holds a certain resonance.

The continent is grappling with the challenge of crafting political and social structures suited to the demands of rapid development while simultaneously re-evaluating, adapting, and, where necessary, transforming its traditional cultural heritage in response to the inexorable forces of modernity and foreign influence. Above these concerns, there is the ever-pertinent question of governance; of the nature of leadership and the ethical foundations of political life. A small glance at Africa’s current predicament suffices to reveal the urgent and indispensable role of the African philosopher. It falls upon him, the philosopher, to lend his voice to the great debate on the most fitting mode of social and political organisation for the continent.

Africa has long struggled with the question of choice—or, more precisely, the discovery—of a viable socio-political system. In this pursuit, the role of “ideology” in national life cannot be ignored. To think of an Africa devoid of philosophical engagement in these matters is to reduce it to a fate dictated by forces unexamined and unchallenged. It is thus clear that philosophy in Africa must not remain a passive exercise in abstraction but an active force shaping the continent’s intellectual and political destiny, its ideology.

Wiredu defines ideology as a set of ideas about what form a good society should take. Such sets of ideas, no doubt, need a basis in the first principle, which is where philosophy enters. There is the other sense of ideology, which is a prefabricated system of doctrines, adopted wholesale by governments as the exclusive foundation for political organisation. In this latter guise, ideology ceases to be a guide for thought and instead hardens into dogma, to be enforced, if need be, through coercion.

If you look around Africa today, you will find that it is politicians rather than philosophers who have tended to propound an ideology. However, these efforts, lacking both conceptual rigour and philosophical grounding, have left no lasting imprint on the intellectual habits of society. It is little wonder, then, that such ideologies, lacking any critical inquiry, have often degenerated into instruments of repression, wielded with brute force rather than reasoned persuasion.

It is, therefore, the duty of the philosopher to oppose the emergence of ideology in this second, authoritarian sense. A society cannot be expected to progress if its people remain bereft of a coherent vision of its highest aspirations. One might, in light of this, be tempted to regard ideology as antithetical to philosophy and an obstacle to development. But true development is not merely a matter of technological advancement; it is, above all, the cultivation of conditions that enable human beings to realise themselves as rational agents. Any ideology that tampers with this fundamental aim is not only philosophically indefensible but a serious betrayal of the very essence of human progress.

Thus, with a coherent and well-defined African philosophy, the future of Africa to stand on equal footing with its more advanced counterparts is certain. Wiredu reminds us that it is the solemn duty of the African philosopher to excavate the intellectual substratum of traditional thought, refine it in light of contemporary African experience, and forge from it a robust philosophical edifice. This endeavour remains ongoing, and the term “African philosophy” must be reserved not for the unexamined inheritance of the past, but for the rigorous intellectual project being shaped by Africa’s finest minds today. It is a philosophy in the making

Few have contributed to this enterprise with the depth and diligence of Kwasi Wiredu. In his relentless intellectual pursuit, he sought to synthesise Africa’s philosophical heritage into a coherent, forward-looking system. He did not provide a final resolution to the questions that troubled him nearly all his life, but his work has emboldened a new generation of thinkers who now carry the torch. Had he lived longer, perhaps he would have untangled the last knots of this grand philosophical puzzle. But fate willed otherwise. On January 6, 2022, this bright son of Kumasi embarked upon that final voyage, to that destination from which, according to both Mark Twain and Ecclesiastes, no traveller ever returns.

***

Read more: Is There an African Philosophy? The Need to Reevaluate African Philosophy