Young African voices are gaining popularity on social media the world over, using these platforms for comedy and political debate – and often for political debate that’s also funny.

One of the new generation of TikTok celebrities in Africa is Charity Ekezie, a Nigerian humourist and journalist. She’s gained 3.3 million followers on TikTok (and 570,000 on Instagram). Her skits poke fun at the world’s perceptions of the continent as backward and barbaric.

Rowland Chukwuemeka Amaefula is a theatre and performance scholar who has analysed Ekezie’s TikToks, her sarcastic brand of humour and how she uses social media as a space for politically relevant performance. We asked him about his study.

Who is Charity Ekezie?

Charity Chiamaka Ekezie is a journalist, influencer and content creator. She studied mass communication in Nigeria before working at a radio station for three years.

Like many Nigerians who took to social media to escape boredom during the COVID-19 lockdown, Ekezie began making creative videos and sharing them. Before TikTok became popular in the country, she had been creating informative content on Facebook and YouTube (where she has almost 1 million subscribers) for years.

She gained fame when she participated in a TikTok trend showcasing the cultural outfits of different African countries. The video went viral. This wasn’t just because of the beautiful cultural dress she displayed but also because of unprovoked attacks from non-Africans who deride her African origin. They posed questions that suggested that Africa is a continent (though some thought it was a country) lacking in resources, technology and modern comforts.

She responded by producing acts that answered these ignorant questions, using humour to mock them. The more questions she was asked, the more videos she produced. Her acts enlighten non-Africans who disrespect and stereotype Africans even when they have not travelled to or read up on life in the continent.

What are her TikTok skits about?

She enacts funny responses to actual questions asked by non-Africans on her social media feeds.

Although she seemingly accepts these stereotypes in her performances, her actions unseat them and cast light on negative perspectives. Asked if there is candy in Africa, for example, she answers that there is, in fact, no candy in Africa – Africans kiss bees and suck their honey out when they want something sweet to eat. She does so standing in front of a table full of candy and eating some.

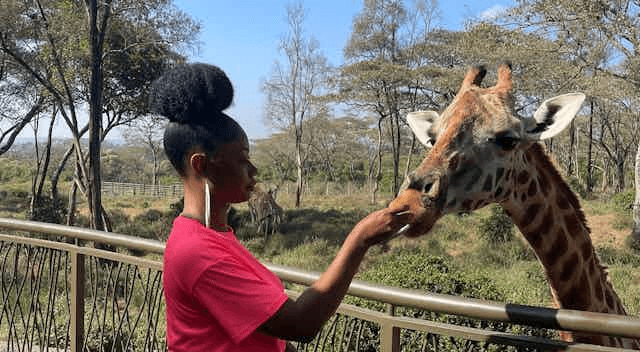

She gives hilarious explanations of how Africans can smell good without perfume, co-habit with wild animals, drink saliva in place of water, or travel long distances by foot. She explains that clean water, cars, aeroplanes or tarred roads don’t exist on the continent – while appearing alongside these things.

A common question she’s asked is about whether it’s safe to visit Africa. In one TikTok she admits that Africa is not safe. In fact, she says, glancing around nervously, a lion is roaming in her vicinity as she speaks. She advises that if the person were to visit Africa, they must be sure to ask for some vanishing lotion at the “border of Africa” so that wild animals won’t see them.

So, Ekezie uses sarcasm as a major instrument for refuting negative stereotypes. Sarcasm is the use of remarks that clearly mean the opposite of what they say. It can be a biting form of humour.

Her responses seem to confirm the wild imagination of the questioner, but in fact reveal the question to be bizarre – and deserving of a bizarre answer. It is through audience laughter in the form of online comments – especially from her followers of African descent – that naive enquirers realise how meaningless their stereotypes and misconceptions are.

What is your analysis of Ekezie’s social media acts?

My study views Charity Ekezie’s TikTok performances as important contributions to ongoing efforts at decolonisation. That’s to say, they undo the damaging effects of colonial rule and European views imposed on Africa.

Before social media, several notable cultural producers were engaged in addressing similar long-standing attempts to demonise Africa. Among these I include Nigerian writer Chinua Achebe, Botswana academic Peter Mwikisa, British dramatist Robin Brooks and Nigerian writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie.

What is spectacular about Ekezie’s strategy is its hilarious nature. I analyse a selection of her TikTok acts to show that her approach is less combative and more entertaining. She dispels ignorant views in a playful way that places the joke on the questioner. She flips the script.

She highlights the need for people who are genuinely ignorant about the continent to carry out basic research before going public with their views. But her comedy goes further. She uses an accessible medium to refuse misconceptions and re-make perceptions of the lived experiences of Africans. I call it a form of political refusal. She refuses to accept typecast narratives pigeonholing Africans as barbaric.

Why does this matter?

Ekezie’s acts are important because they interrupt conscious efforts at demonising Africa and Africans. When such wanton or ignorant attacks are left unanswered, they harden into mainstream portraits.

These portraits simplify the complexity of life in African countries and diminish human beings to stereotypes. Judging by their responses, many of the non-Africans who engage with Ekezie do not even know that Africa is not a country but the second largest and second most populous continent, composed of 54 heterogeneous countries.

This is given added significance by the fact that she is part of a rise in pan-African content on social media and that many of the leading voices are those of African women. Angella Summer Namubiru from Uganda, for example, produces similar content to Ekezie.

These new TikTok stars produce pointedly political perspectives that push back against widespread negative portrayals and projections about Africa – and affirm the creativity, joy and complexity of African life.

***

Rowland Chukwuemeka Amaefula, Lecturer, Department of Theatre Arts, Alex Ekwueme Federal University Ndufu-Alike

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.