For many countries around the world, December is an intense, commercialised period of gift-giving. Not just within families but across all sorts of relationships, such as gifts between buyers and service providers.

Gift-giving, the act of presenting someone with a gift is intended to convey thoughtfulness, appreciation, or goodwill. The gift can be a tangible item, experience, personal time or gesture. It’s an age-old tradition found across cultures and societies, carrying various meanings and functions that help shape human relationships.

I’m the university chair in African philanthropy at the Centre on African Philanthropy and Social Investment at Wits Business School in South Africa. The centre is Africa’s first and only place of scholarship, teaching and research in this field. I’ve undertaken various studies looking at where gifting came from as a human behaviour, and its history in Africa.

Gifting began in Africa when the first humans like us emerged. It then evolved as people migrated and was adapted to fit different cultures. Early examples involved the transfer of cattle or women to seal relationships between groups.

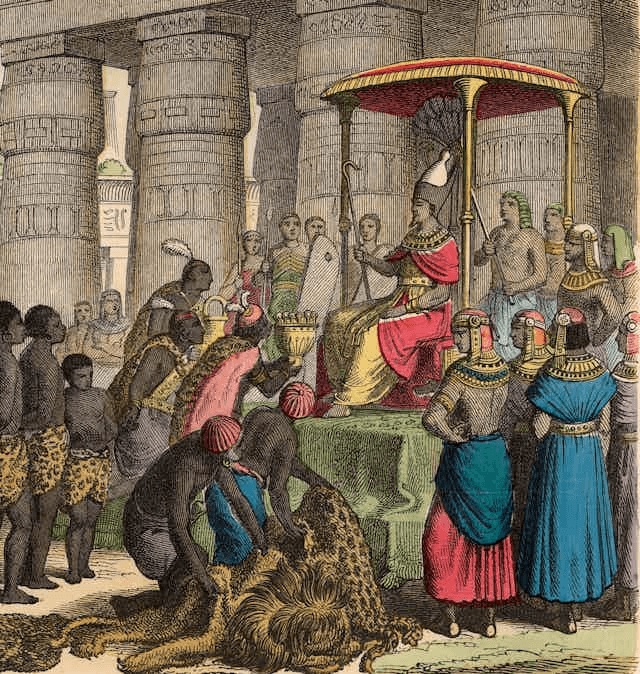

Today, it is exemplified by exchanges of gifts between countries during state visits and has evolved into practices like philanthropy. Giving is something that takes place outside households and celebrations, typically to create or seal relationships.

By examining the full history of giving, we’re able to trace its fascinating evolution and the many ways of showing generosity.

Human cognition

Today’s humans originated in Africa, about 200,000 years ago, developing unique mental (cognitive) abilities as part of their evolution. These governed the way humans interact with each other. Giving complemented other survival mechanisms, like instinctive “fight or flight” response.

Research shows that three types of interactive human socioeconomic behaviours evolved together: selfish, cooperative and selfless. Collectively applied, they enabled groups of hunter gatherers to survive, flourish and grow in numbers. These behaviours appeared in a ratio of about 20% selfish, 63% cooperative, and 13% selfless. This relative ratio endures today.

Gifting is similar to the instinct to cooperate, but it does not necessarily imply that something is expected in return. In other words, giving gifts started as a way of sharing that showed selflessness.

As people migrated around the world, their societies adapted to the conditions they encountered. The mix of selfishness, cooperation and selflessness became woven into diverse cultures.

Emergence of gifting

As humans evolved, more and more complex social relationships developed in bounded territorial spaces. Within Africa, groups become clans, clans become tribes, developing into chieftainships, kingdoms and other types of organised areas.

Here, gifts were important for two reasons.

First, within groups, gifts were structured ways of caring for each other and ensured mutual well-being and growth. Gifts were used to build friendships and connections among equals (horizontal relationships). Gifts also helped create loyalty and respect in relationships with leaders or people in power (vertical relationships). Here, gifts were often equated with an expected “deal”. For example, a gift would earn the support of and protection by those with authority. Or, for example, gifts during ceremonies ensured one’s place within the group.

Second, between separate identity groups, gifts also functioned as a (symbolic) instrument to negotiate and prevent what might otherwise be hostile relationships.

Shift in practices

Islamic expansion in northern Africa and the imposition of rules by European colonisers everywhere altered this landscape. Gifting started to function in different, notable ways.

Islam came into ancient Africa around the seventh century while Christianity spread from what is now Egypt in the first century AD. Each faith recognised an obligation to gift. They introduced new, formalised and institutionalised forms of giving, such as caritas, or Christian charity, and zakat, a Muslim obligation of giving for the needy.

Early in the past millennium, as resistance to colonisation gained traction, gifting practices transformed into a self-defensive strategy. Gifting became one tool to cope and survive under difficult conditions. For example, in east Africa people would exchange food, money and other resources to support both families and the communities they were part of. In Kenya the community practice of harambee (pulling together) sponsored expansion of access to education: an example of horizontal gifting.

End of colonial rule

Colonial rule ended after about 300 years. In the post-colonial era, gifting can be divided into two periods. One can be referred to as “traditional”, dating from about 1960 to 2000. The second, from 2000 onwards, can be called “new age”.

The traditional era loosely corresponded to when many African countries gained political independence, calling for a return to traditional values, societal norms and to self-determination.

African leaders inherited borders that forced together diverse ethnic and language groups, each with different relationships to colonial powers that had to be managed. In many ways, this laid the foundation for the prevalence of Africa’s ethnic patronage in politics today.

For about 30 years of independence, many countries were under single-party rule with politicians relying on vertical gift-like handouts extracted from public resources, to manage internal political tensions. Even after multi-party systems were introduced, this practice continued as a form of political dispensation.

Independence allowed many non-governmental organisations (NGOs), or “givers”, to become involved in development. Instead of focusing on people’s rights, aid was often framed as charity. NGOs used professional, one-way donation models. Despite good intentions, this shift has weakened traditional, community-based contributions as local communities became reliant on external gifts.

Alongside NGOs, big private donors and foundations introduced the idea of “philanthropy” to Africa. This popularised a type of giving that can make traditional, smaller-scale generosity feel less important. It potentially discourages those who can’t give as much.

New era of gifting

This millennium has introduced a new age of African giving, driven by three key factors; dissatisfaction with traditional grant methods, a variety of funding sources, and different approaches and ways to measure success.

One force is a fast-moving diversification of gift-givers. Examples include corporate social investment as well as “philanthocapitalism” – large-scale donations or investments by very wealthy individuals or private organisations. They typically use business strategies to tackle social issues.

Another force is innovation in the design of gift-giving practices. For instance, trust-based philanthropy where funders support recipients they trust without requiring strict contracts or periodic detailed reporting until the next tranche is paid. Another innovation is effective altruism, a type of giving that focuses on making rational, evidence-based investments to create measurable solutions for social problems.

Third is promotion of domestic resource mobilisation. This is the application of Africa’s own assets for its development, which includes diaspora remittances.

Looking back, it’s clear that those giving gifts – in whatever form – should take a more reflective and balanced approach to understanding the role of giving role in Africa’s community and society, especially as a political tool. Doing so can help bring greater accountability of leaders to their citizens.

***

Alan Fowler, Honorary Professor in African Philanthropy, University of the Witwatersrand

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.