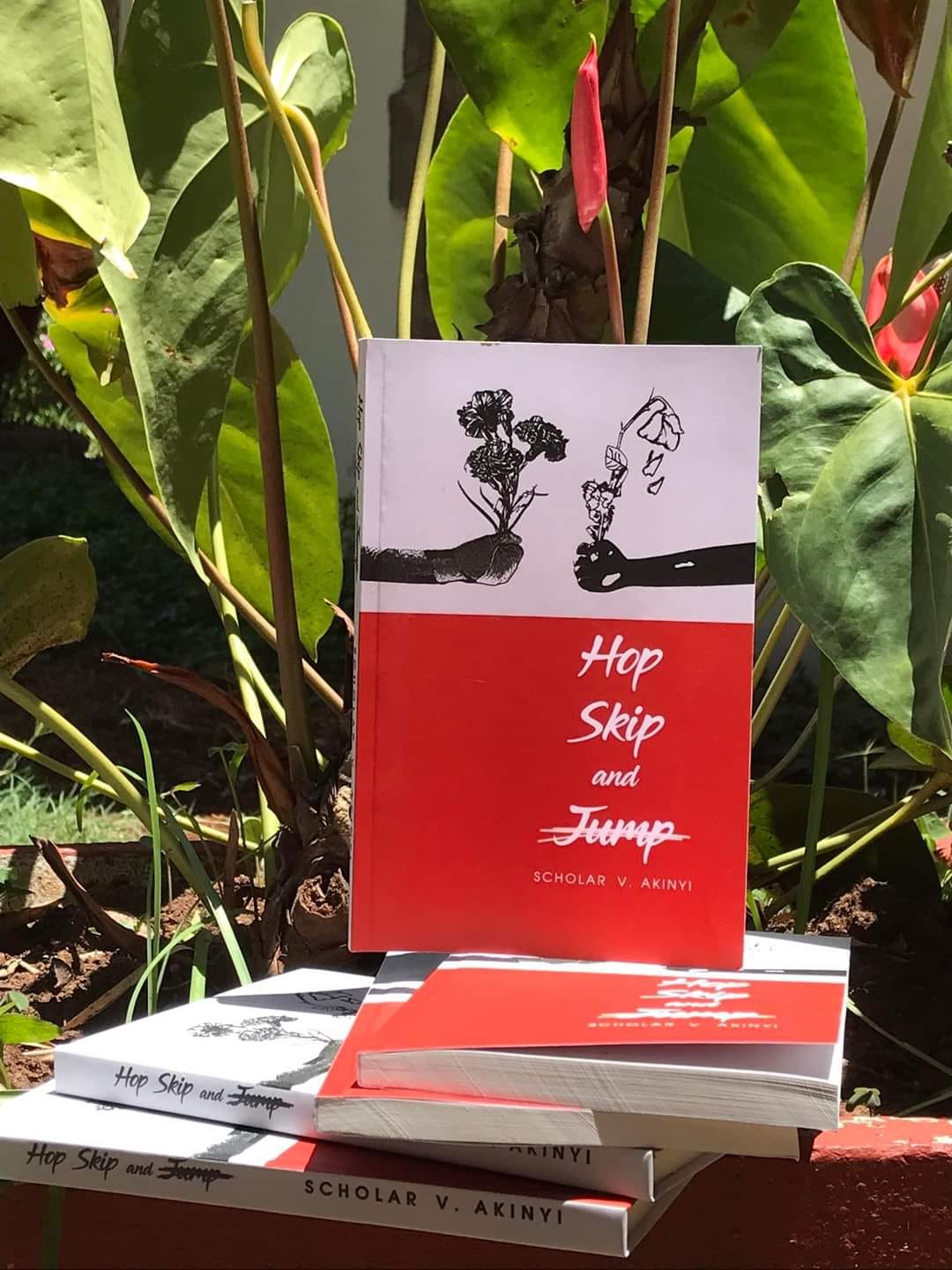

On the evening of December 30, 2007, Mwai Kibaki was sworn in for a second term as President of the Republic of Kenya, and for a moment, only a moment, the country knew a short-lived, chilly quietude that harboured disbelief, mistrust and the sting of betrayal. In the Rift Valley, men were running in the night wielding pangas, out for blood, revenge and a long-awaited opportunity to dispossess their neighbours of their land. In the slums of Nairobi, gangs rose up to govern, ruling with ruthlessness, guided by the concept of shibboleth. A new term entered the national lexicon: IDPs, internally displaced persons; for the outbreak of politically coordinated violence resulted in the making of Kenyans refugees within their own country. Towards the end of January, there was a second wave of retaliatory violence most notably in Naivasha, the setting of Scholar V. Akinyi’s novel Hop, Skip and Jump that is inspired by the bloody events of that terrible, dark time.

During the book launch earlier this year, the author revealed that the book is hardly fictional, that the narrative is her lived reality. She was there, in Naivasha, as a child, 16 years ago. Perhaps this was the most unsettling thing for me as a reader, the knowledge that the story I am reading, though fictionalised, is the history of somebody, of many people in fact, of hundreds of thousands, for about 1,500 Kenyans lost their lives and about 700,000 were displaced from their homes. This country went to war for two months, then just as it was about to fall off the edge into the abyss, the leaders of the two warring sides signed a peace agreement on February 28.

First of all, Hop, Skip and Jump is a children’s book in the exact same way that Harper Lee’s To Kill a Mockingbird is a children’s book. It’s not! Though narrated through the innocent eyes of three children, two boys and a girl, growing up in Naivasha, the themes especially towards the end get too heavy for a children’s book, just like NoViolet Bulawayo’s We Need New Names. The book begins easy enough, concerned with the things of childhood: becoming a prefect, passing exams, writing a lover letter to a girl, receiving a love letter from a boy, looking after the younger siblings, playing, and so on. The world of the adults, just like in many children’s books, is an alien world, and the adults are othered, lack personality, for they only exist in children’s minds to play well-defined roles of father, mother, teacher, tailor, and so on. But the world of the adults intrudes every so often into the tranquillity of the children’s lives, for example, the fact that Christmas seems to be a non-issue this year, because the adults are focused on the drama of the elections, and naturally the children feel this is unacceptable. After all, Christmas is Christmas!

Notable among the stylistic choices by the author is the lack of changing narrative tone or style as the story shifts from one child’s first-person point of view to the next. The three children sound like the same person, and additionally, they do not sound like children completely, for their diction and worldviews seem a little bit more developed than what you would expect from preteens. The author assured me that this was a stylistic choice on her part, that doing otherwise felt not quite right. At first, this seemed like an oversight to me, but later on, when the story began to get gory, I was glad for this regularity, for the unvaried narrative voice provides a throughline of order and familiarity that keeps the reader calm even as the story gets too horrifying. The author’s intuitive decision, in my opinion, serves as a protection of the reader’s psyche from the traumatic events that may be triggering for many, especially parents and anyone who has experienced violence.

The second authorial choice that I appreciated was the epilogue, which I told Scholar felt to me more like a wish fulfilment, an aspiration not just of the character but of the author and of the nation at large. Many authors are learned in the art of breaking readers’ hearts, but fewer know how to repair those hearts. Rather than leave us traumatised, the author was considerate enough to provide a formula for healing and the restoration of patriotic spirit in us. Most notable is the use of sports as a vehicle for the repair of broken national bonds. 2008 was the year Pamela Jelimo won the Olympic gold medal for the 800-metre race at Beijing, a moment that this book made me realise must have been incredibly powerful and full of transformative energy for a nation that was recovering from a civil war. Clearly aware that the epilogue is a wilful choice on her part, the author inserts this poem by Nikkila Ursula just before the closing sentence:

I think we deserve

a soft epilogue, my love.

We are good people

and we've suffered enough.

Take note. We deserve a soft epilogue because we’ve suffered enough. With this statement, Scholar expresses what I believe is the ultimate message of the book. Every sentence in the book is surrounded by a sense of dignity and a pervading empathy. The author, who is present in every sentence (for as I said, no children could write so literately), regards humanity with compassion. She wants compassion for herself and others. We deserve a soft epilogue, my love. We are good people and we’ve suffered enough. Further, note that it is “I think”. It is only a wish! Not a rejection of reality, but the pronouncement of a soul’s softest yet most earnest desire, that there may be compassion for self and others. If Kenyans had compassion for each other, if our leaders had compassion for us, the outbreak of murder, rape, arson and displacement in 2007/2008 would not have occurred. Being a reader who believes in his intuition above all else, I will tell you what I feel. I feel that the entire purpose of this book was for Scholar V. Akinyi to arrive at the end and write that epilogue and say, “I think we deserve a soft epilogue, my love. We are good people and we’ve suffered enough.”