Peter Sexford Magubane, a courageous South African photographer whose images testify to both the iniquity of apartheid and the determination and devotion of those who brought about its demise, passed away at 91 years of age in early January 2024.

Magubane leaves behind a vast archive of extraordinary images, many of which continue to be the signature images of some of the worst atrocities committed by the apartheid regime.

The photographer suffered great losses during apartheid. In 1969, Magubane spent 586 days in solitary confinement. In 1976, his home was burnt down. He miraculously survived being shot 17 times below the waist at the funeral of a student activist in Natalspruit in 1985. His son Charles was brutally murdered in Soweto in 1992.

Despite the pain and suffering he witnessed and experienced, Magubane’s photographs testify to the hope that is at the heart of the struggle for a just world.

Witness to momentous events

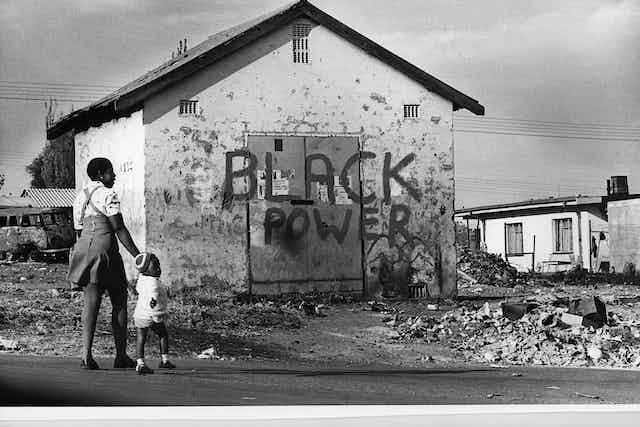

Magubane grew up in Sophiatown, a mixed-race area around 5km from the centre of the city of Johannesburg. He not only witnessed, but also took part in, many of the most significant events in modern South African history.

He was 16 years old when the white supremacist National Party came to power in 1948 and he came of age as the state introduced a series of repressive laws implementing the system of apartheid. These laws were to shape the course of Magubane’s life.

They included the Group Areas Act (1950), which dictated where people were permitted to live based on the colour of their skin, the Population Registration Act (1950), which classified all South Africans by race, and the Native Laws Amendment Act (1952), which required all Black South Africans to carry a “passbook”. Referred to as the “dompas”, the document was used to control and restrict the movement of black South Africans.

In 1955, Sophiatown was demolished, and its 60,000 residents were forcibly removed. Magubane’s family were forced to relocate to Soweto. His images focusing on life in the township were later to form the subject of several of his books.

In 1952, the Defiance Campaign saw widespread non-violent resistance to the hated dompas across the country. It was in this incendiary political atmosphere that Magubane found his calling as a photographer.

In 1954, Magubane began working at Drum magazine as a driver. The magazine, founded in 1951 and modelled on picture magazines like Life and Picture Post, was to take the lead in changing how Black South Africans were represented in the media. Within three months, Magubane had taken up a position as a darkroom assistant. He soon began to work as a photographer under the tutelage of Drum’s chief photographer and picture editor, Jürgen Schadeberg. Magubane rapidly secured his place as one of the great photojournalists of his generation, alongside Alf Kumalo, Bob Gosani and Ernest Cole.

By the mid-1950s, it became mandatory for Black women to carry passes and in 1956, 20,000 women, united under the banner of the Federation of South African Women, marched in protest to the seat of government, the Union Buildings in Pretoria. Magubane documented this march and continued to pay close attention to the central role of women in the struggle against apartheid throughout his career. Many of these images are collected in his 1993 book, Women of South Africa: Their Fight for Freedom.

Between 1956 and 1961, Magubane took photographs of the Treason Trial, which saw 156 national leaders tried for high treason after the adoption of the Freedom Charter at the Congress of the People in Kliptown in 1956. Among the accused were leading members of the African National Congress and of the Congress Alliance, including Walter Sisulu, Nelson Mandela, Helen Joseph, Ruth First and Bertha Mashaba.

During this period, Magubane was arrested four times and frequently harassed and assaulted by the police.

He was one of the photographers who documented the immediate aftermath of the Sharpeville Massacre on 1 March 1960. On that day more than 7,000 people gathered outside a police station at Sharpeville, a place not far from the city of Johannesburg, to protest against being forced to carry passbooks. Arriving without their passes, their intention was to give themselves up for arrest.

Police officers opened fire and shot 13,000 bullets into the crowd. Official records stated that 69 people were killed, and over 300 wounded, although recent reports suggest the casualties were much higher.

Magubane’s photograph of a seemingly endless row of coffins receding into the distance, awaiting burial, their dark wooden surfaces almost white in the sun’s glare, conveys the terrible magnitude of the massacre. Alongside the coffins are a priest in white robes and hundreds of mourners dressed in dark suits. A woman in a black dress stands near the mass gravesite and holds a white cloth to her mouth in a gesture of profound grief.

The image is both chilling and portentous – as curator Okwui Enwezor has noted:

the events of that day produced the picture of the funeral as one of the central iconographic emblems of the anti-apartheid struggle.

Magubane’s images of Sharpeville were published in Life magazine and played a key role in bringing the brutality of the apartheid state to global notice.

On 16 June 1976, young people of Soweto rose up in protest against being forced to learn in Afrikaans. Magubane convinced the students of the importance of producing a visual record of the struggle.

Photographs he took that day were published as a book, Soweto 1976: The Fruit of Fear, to commemorate the terrible events that took place that day, when the police killed between 400 and 700 protesters and injured thousands more.

Among the many powerful images Magubane made at that time is a photograph of two women walking in a dusty street, their faces displaying signs of terrible pain. One of the women has a large tear in her abdomen, an open wound that forms a dark hole at the side of her body. Her slender hands are beautiful, and their perfect smoothness accentuates the brutal rupture where her skin has been broken.

The immediacy of the image is striking and is all the more remarkable with the knowledge that the bullet that pierced the young women’s body had just narrowly missed Magubane’s face.

The archive

Magubane published more than 20 books. In 2018, his work was exhibited in a major retrospective, On Common Ground, alongside that of another renowned South African photographer, David Goldblatt.

In 1999, Magubane was awarded the Order of Meritorious Service by President Nelson Mandela, who stated:

For his bravery and courage during the dark days of apartheid, Peter became a beacon of hope not only to thousands of journalists all over the world but also to millions of people across our country.

He received numerous awards for his work, including the Robert Capa Award (1986), Lifetime Achievement Award from the Mother Jones Foundation (1997), the ICP Cornell Capa Award (2010), and several honorary doctorates. He served as Nelson Mandela’s photographer from 1990 to 1994.

Magubane’s indomitable spirit and compassionate vision live on through his work. Hamba kahle. (Go well.)

***

Kylie Thomas, Senior Researcher and Senior Lecturer (Radical Humanities Laboratory, University College Cork), NIOD Institute for War, Holocaust and Genocide Studies

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.