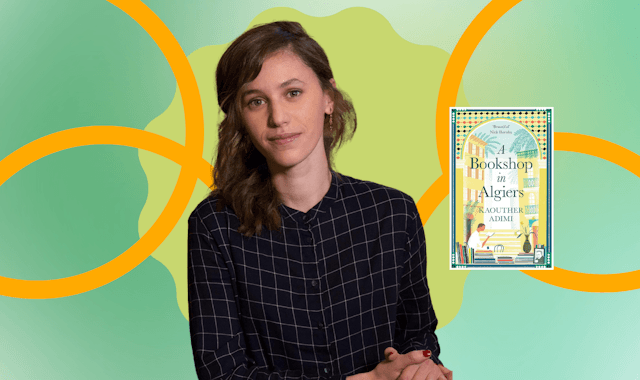

French-Algerian publisher Edmond Charlot is the subject of the Algerian writer Kaouther Adimi’s third novel, and her first to be translated into English.

It was published in 2020 under the US title Our Riches and retitled A Bookshop in Algiers for the UK audience.

Before he reached the heights of fame, the French Algerian author Albert Camus was part of a group of talented thinkers and writers including André Gide, Kateb Yacine and Mohammed Dib. This group’s early works were first printed and sold by the young Charlot.

Adimi’s novel was translated into English by Chris Andrews. It recounts the history of Charlot’s publishing house and bookshop through the eyes of the young Ryad, who is invited to empty out the old Charlot building decades later, so it can be turned into a café selling doughnuts to the nearby university student market.

The tale emerges through intermingling narratives across time and a series of fictionalised first-person diary entries made by Charlot between 1935 and 1961. These entries are punctuated by the huge historical events that would lead to Algeria becoming an independent country in 1962.

As Adimi herself has stressed in interviews, the book is a story about friendship, the importance of literature, the history of the country and city where she grew up, and the cultural “wealth” of writing that exists before any money needs to be made.

However, the novel is also implicitly about Adimi’s own journey as a writer. Specifically, it reflects her experience of moving from a “peripheral” space such as Algiers to more mainstream publishing spaces in the French literary capital of Paris – then to being translated and published elsewhere.

An increasingly well-recognised writer in Algeria, France and internationally, Adimi published her first novel with the then fledgling Algerian publisher Editions Barzakh back in 2010.

Her first book was Des ballerines de papicha – an Algerian expression that is difficult to translate, but that alludes to a coquettish young girl at the centre of the novel. It was a much more experimental text when compared to Adimi’s more recent work. Told through the multiple voices of its Algerian characters, the novel beautifully and poetically captures the joys and tragedies of the everyday lives of a family living in the capital city, Algiers.

While not yet translated for the international market, the book was republished in 2011 with the French publisher, Actes Sud, under the title L’Envers des Autres (The Other Side of Others). In this process, some of the more experimental aspects were changed or removed, with the local Algerian words contained and explained through the insertion of footnotes. What is gained by publishing in France (reaching a wider audience and gaining recognition) is simultaneously a loss in working with a more flexible and experimental Algerian publisher.

This theme of working with a publisher can be found in A Bookshop in Algiers. Discovered by Charlot in 1937, Camus would, alongside other Algerian writers, entrust the fledgling publisher with his first manuscripts. Camus would then correct the works as he sat smoking cigarettes on the steps of the publisher, bookshop and lending library, Les Vraies Richesses (Our True Wealth).

While publishing Camus’s early work represents a clear success for Charlot, the publisher’s thwarted efforts to set up a branch of Our True Wealth in Paris leads him into financial trouble and the ultimate collapse of his beloved publishing house. Unable to pay his authors, Charlot is forced to concede defeat. Camus and the other writers claim back their copyright and are instead picked up by the mainstream Paris publishers.

Here, Adimi’s novel demonstrates the economic pressures surrounding literature and the publishing market. She is seemingly offering a critique of the economic value placed on literary texts above their social and cultural wealth. But it is also an acknowledgement of the writer’s own conflicting desire to remain loyal to her original small Algiers-based publisher, Editions Barzakh.

Naturally, Adimi is also seeking success with the larger Paris-based publishers – and with translations of the novel now exceeding nine languages – she has seen her talent for writing bear fruit. And yet, reading A Bookshop in Algiers, one can’t help but feel something of that earlier poetic experimentation has been lost.

A celebration of small publishers everywhere, with more than a hint of scepticism about the future of literature in a global age, A Bookshop in Algiers is well worth a read. It is a gripping narrative that tells of the highs and lows of Charlot’s life, the political and cultural worlds of Algeria at a pivotal moment in its history, and the struggle of writers and publishers to make it in a world where money trumps culture. Adimi is a brilliant writer and Chris Andrews’ translation expertly renders the novel in English.

***

Joseph Ford, Senior Lecturer, School of Advanced Study, University of London

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.