It is widely known that African researchers are dramatically underrepresented in academic journals. However, it is still astonishing to see this reality starkly represented in numbers.

For the past eight years, we have run the Research, Policy and Higher Education (RPHE) programme, a research and peer-support scheme with Rwandan scholars, through the Aegis Trust. As part of our work, we have analysed 12 leading journals in disciplines relevant to our researcher cohort. We found that from 1994 until 2019, of the 398 articles focusing on Rwanda that appeared in these journals, only 13 were authored or co-authored by Rwandan scholars. That is only 3.3 per cent, amounting to 25 years of post-genocide literature almost entirely devoid of Rwandan voices.

In 2019, the flagship area studies journal, African Affairs, published its first-ever article by a Rwandan. The author, Assumpta Mugiraneza (writing with Benjamin Chemouni), is supported by the RPHE programme.

Four of the journals we examined – Journal of Modern African Studies, Journal of Conflict and Security Law, Journal of Peace Research, and Conflict, Security and Development – regularly publish articles on Rwanda, but are yet to publish a single Rwandan writing about their country.

What explains this level of exclusion? One factor is prejudice on the part of journal editors and peer reviewers, which Rwandan colleagues have encountered for years. It was the need to overcome systemic biases and amplify the voices of Rwandan scholars in global academic and policy debates that led us to establish the RPHE programme in 2014.

Since we launched, experienced Rwandan and non-Rwandan researchers have worked closely with 44 Rwandan authors selected through four competitive calls that generated more than 400 research proposals. The programme has also organised regular theory, methods, writing and publishing workshops for hundreds of participants in Kigali, supporting the wider Rwandan research community.

It is starting to bear fruit.

A body of scholarly work

Our website, the Genocide Research Hub, has just posted the 21 peer-reviewed journal articles and book chapters that have so far emerged from the programme. It has been a rigorous process to reach this point. The authors first produced working papers and policy briefs. These were honed through discussions with their programme colleagues and at public events in Kigali and London. Only then were they submitted to peer-reviewed journals. Over the next year, these working papers generated a further tranche of academic publications.

Collectively, these pieces represent an important body of scholarly work on various themes. These include ethnicity, indigeneity, migration, citizenship, gender relations and language politics. Authors also delved into debates over younger generations’ inherited responsibility for the 1994 genocide against the Tutsi.

The publications highlight the impressive research being conducted by Rwandan authors, who for too long have been sidelined in debates about Rwanda and other conflict-affected societies.

Numerous barriers

Rwandan authors face numerous barriers. Some are domestic and widely acknowledged. The country aims to become a regional high-tech hub. So, the Rwandan government emphasises the science, technology, engineering and maths subjects. This has led to the chronic under-funding of the social sciences.

Like their colleagues across East Africa, Rwandan academics’ enormous teaching and administrative loads leave little space for research and writing.

Less recognised, however, are the power dynamics in global academic and policy circles. International journal editors, peer reviewers and research fund providers routinely exclude Rwandan voices. This is driven by a pervasive view that Rwandan authors based in Rwanda cannot produce independent and rigorous research in such a repressive political environment.

These structural biases need to be systematically addressed if institutions and publications based in the global north are serious about the “decolonising knowledge” agenda.

The significance of the academic publications produced through the RPHE programme, though, is not simply that they were written by Rwandans. Crucially, these authors have begun to reorient the substance of scholarly debates about Rwanda, and broader peace and conflict issues.

Our calls for proposals asked Rwandan researchers to independently determine the themes and methods of their research, reflecting their deep knowledge of the political, social, cultural, historical and linguistic context. By doing so, they have introduced new themes, angles and insights that greatly enrich the academic literature.

New insights

To take one example, two journal articles by Richard Ntakirutimana – a member of the Rwandan Batwa community – highlight the challenges the Batwa have faced since the Rwandan government placed them under its “Historically Marginalised Peoples” banner in 2007. This category includes guaranteed parliamentary representation for women, people with disabilities, Muslims and the Batwa. However, it conflates Batwa's concerns with those of other marginalised communities in Rwanda.

Many of the Batwa community are highly wary of researchers. But Ntakirutimana was able to conduct extensive interviews with members of the community near the forests bordering Uganda and the Democratic Republic of Congo. His respondents roundly criticised the “Historically Marginalised Peoples” framework. They demanded that the government policies be tailored more specifically to the plight of the Batwa.

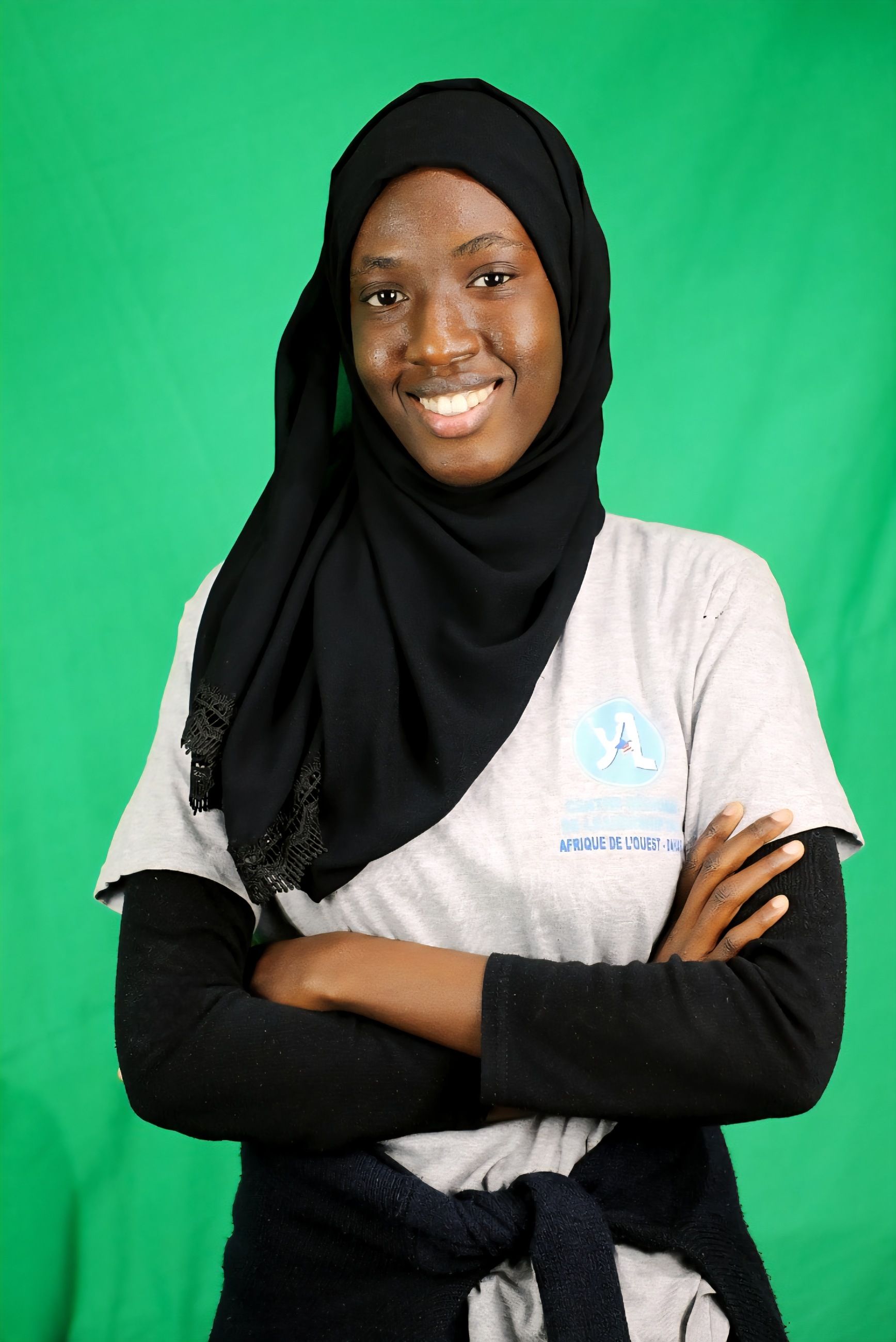

Researchers explore perspectives beyond the capital city, Kigali, giving voice to various Rwandan communities’ experiences. Phil Clark

Researchers explore perspectives beyond the capital city, Kigali, giving voice to various Rwandan communities’ experiences. Phil Clark

When Ntakirutimana presented his research at an RPHE conference in Kigali, his findings generated vociferous push-back from Rwandan policymakers. His work, and that of other authors from the programme who have presented at public events, challenges a widespread perception of Rwanda as a closed political system. Here, independent research and public debate on politically sensitive topics are perceived to be almost impossible.

Meanwhile, across a wide range of topics and disciplines, the articles published by other RPHE researchers explore an overarching theme largely ignored by non-Rwandan authors: the prevalence of intra-family and inter-generational conflicts since 1994.

These researchers focus on genocidal legacies and the impact of post-genocide social transformation in intimate family spaces, which are difficult for non-Rwandan researchers to access. Their work, thus, provides vital perspectives on less visible features of Rwandan society.

Also Read: Seven Narratives We Must Change About Africa

A gradual shift

The highly talented Rwandan social science research community is beginning to gain the global platform it deserves. This shift is vital for Rwandan researchers. It benefits others, too, by producing fresh insights and challenging the structures that, for years, stymied these critical voices. More initiatives of this kind are essential if calls to decolonise knowledge are to become more than comforting blandishments.

Felix Mukwiza Ndahinda, Honorary Associate Professor, College of Arts and Social Sciences, University of Rwanda; Jason Mosley, Research Associate, African Studies Centre, University of Oxford; Nicola Palmer, Reader in Law, King's College London; Phil Clark, Professor of International Politics, SOAS, University of London, and Sandra Shenge, Director of Programs, Aegis Trust

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.